Excellence and Diversity – Disciplinary Breadth in Competition

A statistical review of the involvement of subject areas in the Clusters of Excellence in the second round of the Excellence Strategy of the German federal and state governments

The decisions in the second round of the Excellence Strategy were made at the end of May 2025. From January 2026, a total of 70 clusters will receive new or continued funding. This data story focuses on the question of which subject areas are involved in these clusters and how their interplay shapes the interdisciplinary research profile of each cluster.

Two key questions guide the discussion around the involvement of subject areas in the Excellence Strategy: 1). To what extent are individual subject areas involved: is it primarily the life sciences and natural sciences that benefit from favourable conditions for their research? Is the programme mainly geared towards large subject areas? Does it exclude smaller subject areas, potentially even explicitly? and 2). To what extent do Clusters of Excellence live up to their aim of promoting cross-disciplinary collaboration – in other words, interdisciplinary research: are clusters involving multiple subject areas the norm or the exception? Are there subject areas that are particularly conducive to interdisciplinary cooperation? This data story offers some initial answers to these questions and presents relevant supporting material.

Comparison of the subject-specific focus of the Clusters of Excellence with the subject distribution of general DFG funding activities

The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) has access to a particularly strong data base when it comes to the subject distribution found across DFG-funded research as a whole – in terms of both breadth and depth. For the majority of funding programmes, this is due to the DFG’s clearly subject-oriented processes of proposal review and evaluation, which have been in place since the organisation was founded in 1920. In 2003, the previously established review committees were restructured into the current system of review boards. Since then, the review process has been carried out by individually selected reviewers. Members of the review boards perform a quality assurance function and issue funding recommendations based on the reviews submitted. There are currently 49 review boards, subdivided into 214 subject areas, with at least two experts responsible for each subject area.

For DFG statistical purposes, the fact that most funding proposals are assigned to specific subject areas makes it possible to conduct highly detailed subject-based analyses. One prominent example of this is the Funding Atla(externer Link) report series, published every three years, which presents comprehensive statistics on the subject-specific funding profiles of German higher education institutions (HEIs) and non-university research institutions (cf. Glossary of Methodological Term(externer Link)).

For the purposes of this data story, data on the subject distribution of the DFG’s general programme portfolio provide a valuable basis for comparison. Figure 1 below shows how the relative shares compare across 14 research areas: firstly for the 70 Clusters of Excellence funded in the second round of the Excellence Strategy, and secondly for all projects under way in 2024 within subject-classified funding programmes.

First of all, there is an almost exceptional degree of alignment between the research area shares of the Clusters of Excellence and those of general DFG funding in the humanities and social sciences, in biology, and in four out of five research areas of engineering sciences. The only notable exception is the research area of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, which appears underrepresented in the Excellence Strategy – accounting for just 1 percent of clusters compared to 4 percent of ongoing DFG-funded projects. By contrast, physics shows an above-average affinity with the Clusters of Excellence funding line (accounting for 17 percent of clusters, compared to just 8 percent across general DFG funding). Meanwhile chemistry (4 vs. 6 percent) and medicine (19 vs. 25 percent) are slightly underrepresented within the Excellence Strategy. On the whole, however, the subject profile of the 70 Clusters of Excellence closely reflects that of general DFG funding.

Comparison of the subject-specific focus of the current and previous funding phases of the Clusters of Excellence

Figure 2 additionally enables a comparison with the first funding phase. Here again, the distributions are very similar, primarily due to the fact that 45 of the 70 clusters in the second phase are in receipt of continued funding. Social and behavioural sciences, medicine, materials science and engineering are slightly more prominent in the current round, while chemistry and the field of mechanical and production engineering are somewhat less represented. On the whole, however, the differences in terms of the share of each research area are minimal.

Subject coverage among the Clusters of Excellence compared to the subject distribution of university professorships

How does the subject profile of the Clusters of Excellence compare with that of professors at German universities? Additional data sources and classification systems were consulted in order to address this question. In addition to information on the subject classification of proposals, the DFG also records data on the disciplinary backgrounds of the researchers involved. This happens indirectly via the subject area of the institute at which each individual is employed at the time of proposal submission. For each Cluster of Excellence, the DFG collects data on up to 25 Principal Investigators (PIs). The DFG’s information system GEPRI(externer Link) identifies which PIs involved in a given cluster are affiliated with which institutes and subject areas (from 2026 onwards for newly funded clusters). The subject-specific classification of these institutes can be retrieved via GERi(externer Link), the information system on research institutions in Germany.

The subject-specific classification of institutes is based on the subject classification system used by the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis). At the detailed third level, this system distinguishes 648 units, of which 573 correspond directly to subject areas (cf. Glossary of Methodological Term(externer Link)). The following analysis focuses on the second level, which aggregates teaching and research fields (TaR). For the reporting year 2023, Destatis provides data on professorships at German universities for a total of 59 subject-specific teaching and research fields. 25,558 professorships are recorded in total, to which 1,714 of the 1,740 PIs can be matched.

It is worth noting first that of the 59 teaching and research fields (TaR) defined in the Destatis classification system – which forms the basis for this analysis – only seven show no recorded participation by Principal Investigators (PIs). This means that approximately 88 percent of the TaR categories identified by Destatis are represented in the Clusters of Excellence. Figure 3 presents data for 46 subject-specific TaRs in which two or more PIs are involved. Subject areas for which no PI participation in Clusters of Excellence is recorded include education, sports science and design.

Approximately 88 percent of all teaching and research fields (TaR) distinguished by Destatis are involved in Clusters of Excellence. An above-average level of participation is evident in Physics/Astronomy, with 1,319 professorships reported and 292 participating PIs.

In the figure, the line plotted indicates the expected relationship between the number of professors and the number of PIs per TaR – with subject areas above the line having more PIs than might be expected given their staffing levels, and those below the line having fewer.

All in all, a strong correlation is observed between the number of professors and the number of PIs per teaching and research field. Statistically, this is reflected in a relatively high Pearson correlation coefficient of R = 0.69. Yet there are some notable outliers. Physics and astronomy are significantly overrepresented in the Clusters of Excellence – 292 PIs are recorded for 1,319 professorships. In the life sciences, biology shows above-average participation, as does computer science as a subject area within the engineering sciences. By contrast, the humanities and social sciences contribute proportionally fewer PIs than would be expected relative to their professorial base. Slightly above-average representation is seen in administrative sciences, information and library science, cultural studies, and the broader category of law, economics and social sciences.

Involvement in the Excellence Strategy in relation to third-party funding volume per Teaching and Research Field

How does subject area involvement in Clusters of Excellence relate to third-party funding activity? Here again, data from Destatis provides useful indicators. According to the 2023 survey, German universities secured a total of €7.1 billion in third-party funding across the 59 teaching and research fields (TaR) for which professor numbers are available (not limited to DFG funding, cf. Glossary of Methodological Terms). There is significant variation between subject areas, from less than €500,000 in the fine arts to nearly €900 million in mechanical and process engineering.

For the analysis that follows, the 59 teaching and research fields were grouped into five categories based on their absolute third-party funding volumes. The number of professors in each category was then compared with the number of PIs participating in Clusters of Excellence.

The pattern that emerges from Figure 4 is clear: in TaRs with low levels of third-party income there are 2.7 PIs per 100 professors, while in those with very high levels of third-party funding, the figure rises to 9.9 PIs per 100 professors. One striking observation is the significant jump between the two most third-party-funded TaR groups. This suggests that subject areas with consistently strong third-party funding performance also show higher levels of involvement in the Excellence Strategy.

The disciplinary diversity of the Clusters of Excellence

While the preceding sections focused on the general involvement of different subject areas in the Excellence Strategy, the analysis that follows turns to how they are combined. As before, the analysis is based on information regarding the disciplinary backgrounds of the Principal Investigators (PIs) involved in approved clusters. We begin by looking at how many teaching and research fields (TaR) are represented among the up to 25 PIs per cluster. Figure 5 provides insights here, since it differentiates clusters by scientific discipline.

A generally high level of TaR involvement is evident. Across all clusters, the average number of TaRs represented is 6.5 per cluster. The distributions shown in the figure differ significantly by scientific discipline, however: In the natural sciences, for example, TaR participation tends to be moderately broad – most clusters in this field involve PIs from 2 to 4 TaRs. By contrast, the other three scientific disciplines show considerably broader participation: in the humanities and social sciences as well as in the engineering sciences, there are seven clusters each that draw on 10 or more TaRs, with the maximum reaching 15.

The disciplinary breadth of the Clusters of Excellence is considerable. On average, 6.5 teaching and research fields (TaR) are involved in a Cluster. Whereas the natural sciences are typically characterised by moderately broad TaR participation, the other three scientific disciplines generally have a broader base.

How widely are the nets cast in terms of drawing in researchers from different disciplines? Figure 6 offers the relevant insights here: it shows how many scientific disciplines the teaching and research fields involved in each cluster are distributed across.

In this comparison, the humanities and social sciences again stand out for their breadth, as do the engineering sciences. In a total of more than 60 percent of all clusters, the participating PIs come from three or more scientific disciplines. In the engineering sciences specifically, there is not a single cluster assigned exclusively to one scientific discipline.

Subject area size and involvement in Clusters of Excellence

It is often considered problematic that the programmes of the Excellence Strategy – and its predecessor, the Excellence Initiative – tend to be more tailored to large subject areas than to small ones. It is certainly true to say that large subject areas do enjoy certain advantages, as they generally have well-established local structures in place that are helpful when it comes to organising collaborative ventures involving large numbers of researchers. This does not mean that small disciplines are excluded, however, as demonstrated by a study conducted by the DFG based on data provided by the Small Disciplines Research Centre in Mainz (www.kleinefaecher.d(externer Link), in German only). A comparison of involvement in various DFG programmes revealed that the Excellence Initiative was particularly successful in integrating members of small disciplines into cross-disciplinary consortia (cf. DFG 201(externer Link)).

No comparable data is yet available for the 70 clusters funded in the second round of the Excellence Strategy. However, an initial approximation can be made by examining how often individual Destatis-classified subject areas (third level of the classification system) are used to categorise institutes in the DFG's institutional database – extracts of which are published via the GERiT information system (cf. Glossary of Methodological Term(externer Link)). Figure 7 below presents this data, grouping the total of 527 subject areas into five frequency classes. Subject areas associated with a small number of institutes are considered small, while those with numerous institutes are treated as large.

The nearly 400 institutes in category 1 (small number of institutes) cover a wide range of subject areas commonly associated with the notion of “small disciplines” – including Slavic studies, Sorbian studies, papyrology and architectural history, for instance. This category also includes numerous subordinated subject areas such as poultry diseases (veterinary medicine), legal IT (law), and historical education research (education sciences). The picture is clearer for large subject areas: category 5 includes just under 10,000 institutes, encompassing business administration and economics, general social sciences/sociology, general computer science, and public law, for instance.

As the figure indicates, there is at best a weak correlation between subject area size and participation in clusters. It is true that subject areas with only a few institutes are slightly less frequently represented among Clusters of Excellence than those with large numbers of institutes. But the differences are minor, and the highest participation rate is found among subject areas in the second-smallest size category. There is no evidence to suggest that small subject areas are excluded from the Excellence Strategy.

Nonetheless, a more in-depth analysis at a later stage would certainly be worthwhile, directly comparing officially designated small disciplines (as defined by the Mainz classification) with other subject areas. The present analysis should be understood as an initial approximation.

Interdisciplinarity within the Excellence Strategy

As in previous sections, the final analyses presented here are based on the lowest level of the Destatis subject classification system.

A few figures provide context here: The Principal Investigators (PIs) involved in the 70 Clusters of Excellence, as recorded in the DFG’s proposal data, are spread across 263 subject areas (see Glossary of Methodological Term(externer Link)). This means that through the clusters, the Excellence Strategy draws in researchers from nearly half of all subject areas distinguished at the most granular level of the classification system (N = 573). Among them are 74 subject areas represented by only a single person in exactly one cluster, while at the other end of the spectrum there are more than 90 subject areas with at least five PIs involved in two or more clusters.

Download of Figure (interner Link) I Interactive versio(externer Link) (in German only)

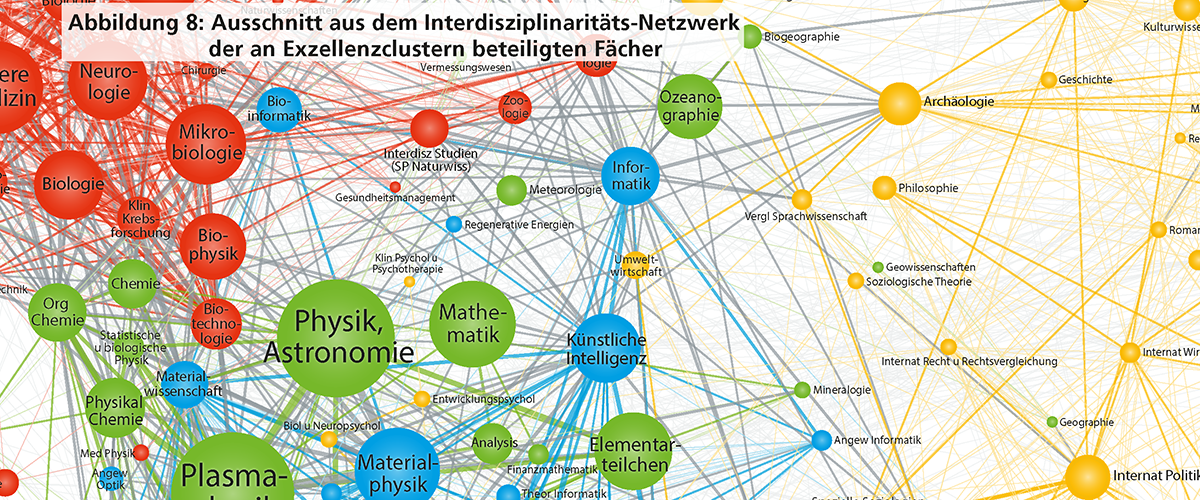

In the first round of the Excellence Strategy, the DFG published a statistical report that – like the current analysis – used the PI-based method to visualise the interdisciplinary structure of the Excellence Strategy I in the form of a network graph (cf. DFG 2019(externer Link)). This was based on visualisations used in the Funding Atlas series, notably the 2015 edition, which included a thematic focus on interdisciplinarity in graduate schools (GSC) and Clusters of Excellence (EXC) under the predecessor programme, the Excellence Initiative (ExIn) (cf. DFG 2015: 172(externer Link)). Figure 8 updates this network based on data on the subject areas of the PIs involved in the second round of the Excellence Strategy.

The figure positions the subject areas shown and their interrelations using a spatial calculation that seeks to place closely interacting subject areas near to each other and locate those that are central – either to substructures or to the network as a whole – towards the centre of the layout (see Glossary of Methodological Term(externer Link) for further guidance on interpretation).

An interactive versio(externer Link) (in German only) of this figure is also available that enables users to select individual subject areas and explore their specific connections within the network. Overall, the network graph displays a structure already familiar from the analysis of the first round of the Excellence Strategy:

- The network is highly dense – in other words, a large number of subject areas are directly connected to many others, with connections defined as shared participation in at least one cluster.

- The network is shaped by a substructure that strongly reflects the four scientific disciplines distinguished by the DFG.

- The central positioning of the subject area physics/astronomy can be regarded as almost canonical. This subject area, along with others related to physics, is generally particularly well suited to collaboration with researchers from a wide range of scientific disciplines. This may also help explain why – as previously noted – physics demonstrates a particularly strong affinity with this funding programme, where there is an explicit focus on interdisciplinarity.

AI researchers play a key role in the interdisciplinary network of the Excellence Strategy

One indicator of the dynamic nature of cross-disciplinary collaboration is the central position of the subject area Artificial Intelligence. In the network graph from the first round of the Excellence Strategy, this subject area was already positioned near the centre, although still as a relatively small “node”, i.e. with fewer researchers and fewer links, and thus somewhat inconspicuous. Now there are 27 PIs involved in Clusters of Excellence who are based at institutes specialising in artificial intelligence. With connections to a total of 119 other subject areas, Artificial Intelligence is by far the most highly networked subject area in the overall structure – a fact also reflected in its high betweenness centrality, a measure used in network analysis to quantify structural centrality (see Table 1 and Glossary of Methodological Term(externer Link)).

It is important to emphasise one point here, particularly in relation to this subject area: whether a person is based at an institute for artificial intelligence or whether their primary research focus lies in artificial intelligence – regardless of their institutional affiliation – are two distinct classifications. That said, especially in the case of very recently established subject areas like Artificial Intelligence, there is a high degree of dynamism here, drawing on influences from across the disciplinary spectrum and using them to advance further development. Even so, the subject area’s central position is more than merely symbolic: Artificial intelligence clearly plays a major role in current research, and the PI data from the Excellence Strategy clearly confirm that this subject area holds a central place within the programme – a particularly central place in fact.

Artificial intelligence (AI) plays an important role in current research and is by far the most interconnected subject area within the interdisciplinary network of the Excellence Strategy. The central position of some subject areas in the humanities and social sciences is also noteworthy.

The distinctive networking role of selected subject areas from the humanities and social sciences

Table 1 lists additional subject areas with high betweenness values. Of particular relevance to the discussion around the role of the Excellence Strategy for the humanities and social sciences (or perhaps more fittingly: the role of the humanities and social sciences for the Excellence Strategy?) is the fact that these account for 11 of the 25 subject areas with the highest betweenness values – and therefore clearly dominate the field (life sciences = 7, engineering sciences = 6, natural sciences = 1). This does not mean to say that these subject areas are pivotal in defining the research activities of numerous clusters. But they do serve as crucial bridges between a wide range of disciplines – in effect making interdisciplinary collaboration viable in practice. This is particularly evident in the case of the highest-ranking subject area, “Specialised Sociologies”. This category is applied to sociological institutes focused on specific research areas such as agricultural sociology, sociology of religion and organisational sociology. It is standard practice for sociologists with this type of specialisation to collaborate with subject-matter experts within the relevant domains in order to explore shared research questions in greater depth. But subject areas clearly located within the humanities – such as philosophy, the history of science and regional history – likewise prove to be particularly well-positioned in terms of their subject-based connectivity.

Looking ahead to the future

This data story is based primarily on data relating to the Principal Investigators (up to 25 per cluster) involved in the Clusters of Excellence, and on the subject areas associated with the institutes at which the PIs are reported to be employed according to the proposals submitted. As previously documented for the first round of the Excellence Strategy – as well as for the previously funded Clusters of Excellence and graduate schools under the Excellence Initiative (cf. WR and DFG 201(externer Link)) – the DFG holds an additional data source that has not yet been incorporated here. This source offers even more detailed insights into subject-specific participation than the PI data considered in this data story.

It is the annual monitoring survey in coordinated programme(interner Link), which gathers data on the researchers involved in Collaborative Research Centres, Research Training Groups, Research Impulses (since 2024), and Clusters of Excellence. This survey collects data annually on nearly 50,000 individuals and participation in it is mandatory. For the Excellence Clusters funding line alone, the most recent 2024 survey covered nearly 15,000 individuals. Once the initial recruitment phase for the new clusters is largely complete, this data will be used to enable more in-depth analyses of the disciplinary diversity and interdisciplinarity of the Excellence Strategy – based on a much broader dataset and with the possibility of regular annual updates.

Further Information

DFG, 2015: Funding Atlas 2015. Key Figures on Publicly Funded Research in Germany(interner Link)

Wissenschaftsrat und DFG, 2015: Bericht der Gemeinsamen Kommission zur Exzellenzinitiative an die Gemeinsame Wissenschaftskonferenz(externer Link) (in German only)

The following alphabetically arranged index of key terms provides further information about the sources of data used for the data story and the methods used for data preparation and analysis.

Destatis subject classification system

The subject classification system used by the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) for staff statistics, which also applies in an adapted form to statistics on university finances, students, examinations and doctoral researchers, is used in the → DFG institutions database to classify institutions by subject. The Destatis subject classification system (as of 2024) is hierarchical, comprising nine subject area groups, 83 teaching and research fields (TaR) and 648 research areas. To avoid confusion with the terminology used in the → DFG subject classification system, this analysis uses the term “subject area” rather than “research area” when referring to Destatis data. For an overview of levels two and three of the Destatis classification, along with a concordance between Destatis subject areas and the research areas in the → DFG subject classification system, see Table Web-3(externer Link) (in German only) of the Funding Atlas 2024. Of the 83 teaching and resesarch fields (TaR), 69 are subject-related; the remaining categories refer to general university administration (central units) and are excluded from the analyses. This also applies at subject area level: of the 648 Destatis subject areas, 573 are subject-related, while the other 75 relate to administrative or infrastructural categories.

DFG institutions database

The institutions database maintained by the DFG represents the hierarchical structure of universities and non-university research institutions, e.g. faculties, departments, institutes, professorships and subject areas. In addition to further information such as institution type, the institutions database also includes a subject area classification of each institution in line with the → Destatis classification system (at the third level – research areas).

For this data story, the subject classification of an institute is used to assign Principal Investigators (PIs) to the relevant subject area. The term “institute” here broadly includes chairs, professorships, research units and similar organisational entities. Only the lowest-level organisational units in the hierarchy are considered in the analysis, and only those at universities, including university hospitals. The subject areas are derived from the third level of the → Destatis subject classification system.

The number of institutes classified on a subject area basis is used to analyse the effect of subject area size. The following size categories are applied:

- Size category 1: 1 to 5 units. This applies to 134 subject areas and covers 393 units.

- Size category 2: 6 to 20 units (138 subject areas and 1,676 units)

- Size category 3: 21 to 40 units (103 subject areas and 3,077 units)

- Size category 4: 41 to 80 units (96 subject areas and 5,540 units)

- Size category 5: more than 80 units (56 subject areas and 9,575 units)

Extracts from the DFG’s institutions database can be accessed online via the information system GERiT – German Research Institution(externer Link).

DFG subject classification system

The DFG subject classification system distinguishes between a total of four levels: 214 subject areas, 49 review boards, 14 research areas and four scientific disciplines. The report is based on the current subject classification system, valid from 2024 to 2028. See her(Download) for the full subject classification system, including the breakdown at the level of all 214 subject areas. The subject classification system maps the operational structures of DFG proposal processing in terms of its subjects and review boards.

Network analyses

The network visualisation shows in which scientific disciplines Principal Investigators (PIs) have worked or are currently working in Clusters of Excellence, and in which research area constellations they have collaborated or are collaborating within these clusters. Research areas are assigned to individual PIs based on data from the DFG institutions database, referring to the institute at which a PI was employed at the time of proposal submission. Colour coding of the research areas is based on a classification that assigns them to one of the four scientific disciplines used by the DFG. Research areas that could not be assigned to any category of scientific discipline were excluded from the analysis. This mainly concerns IT centres and other central facilities.

The visualisation is based on data for 1,663 Principal Investigators (PIs)involved in Clusters of Excellence during the second funding round of the Excellence Strategy. These PIs were classified by research area and were assigned to teaching and research fields (TaR) that include at least two individuals.

In the network map, each node represents a research area. The size of the node corresponds to the number of associated PIs. The lines linking two nodes indicate that PIs from both research areas are jointly involved in one or more clusters. The thickness of the line increases according to the number of these cross-disciplinary connections. The connection thickness is derived from the number of joint cluster participations between two research areas. For example, if PIs from economics and international politics appear together in three clusters, the resulting line has a thickness of three.

The Force Atlas 2 algorithm was used to determine the spatial positioning of nodes. This ensures that research areas with strong direct or indirect connections are positioned close together, and that research areas central to a given substructure – or to the overall structure – appear at the centre of that substructure or structure.

The interactive network view offers several helpful features for orientation: a search function allows users to locate research area names or abbreviations. Mouseover on a node displays a tooltip with additional information – including the number of associated PIs and the number of clusters in which at least one PI from that subject area has participated or is currently involved. The network can also be filtered by scientific discipline, allowing users to highlight any subject-specific focus within each scientific discipline.

The visualised network includes only the 192 research areas with at least two assigned PIs (192 nodes, 3,206 lines). However, for the calculation of the following network metrics (measures of centrality), all available research areas were included – including those with only one PI – resulting in a total of 263 nodes and 4,157 lines:

- Betweenness centrality

Betweenness centrality indicates how frequently a node (research area within the data story) lies on the shortest paths between other nodes. A node has a high level of betweenness centrality when it serves as a connector between many other nodes – in other words, when it controls important paths of interaction within the network. Research areas with high betweenness centrality are therefore especially significant in terms of the flow of information and network connectivity. - Degree centrality

This indicates the number of research areas with which direct links exist – defined as co-participation in at least one Cluster of Excellence.

Professors (university staff)

The data on university staff is provided by the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) and describes the situation as at 1 December 2023. The staff figures used refer to full-time professors. According to the Destatis definition, professors are all persons with a grade of C4, C3, C2, W3 or W2, junior professors and full-time visiting professors. The staff data used in the data story does not represent full-time equivalents, but rather the number of employed persons (head count). The analyses include only professorial staff at universities (including universities of education and theology) and university hospitals, in accordance with the classification used by the Federal Statistical Office.

Principal Investigator method

For each Principal Investigator named in the Cluster of Excellence proposal (including cluster spokespersons, deputy spokespersons, and participating researchers), the institute of employment is first identified. The relevant research area is then assigned to this PI based on the institute's classification in the → Destatis subject classification system used in the → DFG institutions database. A concordance with the DFG subject classification system also allows assignment to one of the DFG’s scientific disciplines. Each cluster was permitted to designate up to 25 PIs in its proposal.

Ongoing DFG funding

For the comparison between the subject distribution in the Clusters of Excellence and that of general DFG funding, all funded projects with an approved funding period that includes the year 2024 were taken into account.

Third-party funding volume

The data on third-party funding volumes was provided by the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) and refers to the year 2023. According to the Destatis definition, third-party funding includes income from all external sources (for further information please refer to this articl(externer Link)). This data was made available as a special analysis at the level of teaching and research fields (TaR) (→ Destatis subject classification system) and applies only to universities (including universities of education and theology, as well as university hospitals). Only those 59 TaRs for which Destatis also provides data on university professors were included in the analysis.

The size categories used in the analysis (based on the 2023 reporting year) are as follows:

- Size category 1: up to less than €12 million in third-party funding. This applies to 12 TaRs with a total of €72.5 million in third-party funding.

- Size category 2: €12 million up to and including €25 million (12 TaRs, €213.4 million in third-party funding)

- Size category 3: €26 million up to and including €53 million (11 TaRs, €445.2 million in third-party funding)

- Size category 4: €54 million up to and including €160 million (12 TaRs, €1,133.8 million in third-party funding)

- Size category 5: €161 million and over (12 TaRs, €5,227 million in third-party funding)

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. (2025). Excellence and Diversity – Disciplinary Breadth in Competition. DFG Data Stories, Version 1.0, 28.7.2025. www.dfg.de/datastory/exstra-diversit(interner Link)

Version 1.0 vom 29.08.2025

Contact

| E-mail: | Juergen.Guedler@dfg.de |

| Telephone: | +49 (228) 885-2649 |