The 1928 Pamir expedition

The public image of the Notgemeinschaft was shaped by three “Community Projects” in particular: the expedition on the survey ship Meteor from 1925 to 1927, the Pamir expedition in 1928, and the expedition to Greenland in 1930/31.

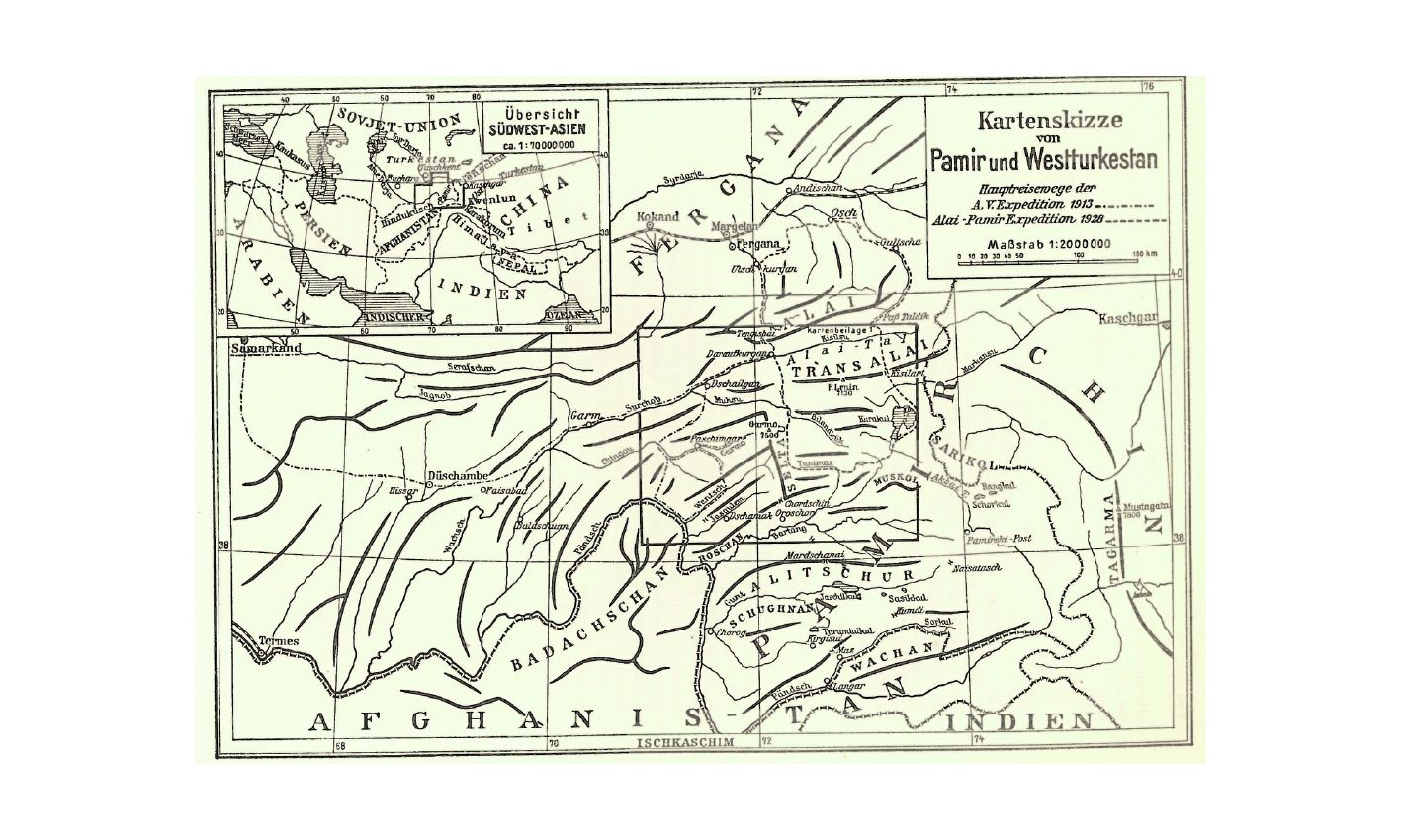

The Pamir expedition was funded jointly by the Notgemeinschaft and the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Eleven German and eleven Russian researchers traversed a largely unknown mountainous region in the south-eastern Soviet Union bordering Afghanistan and China for five months.

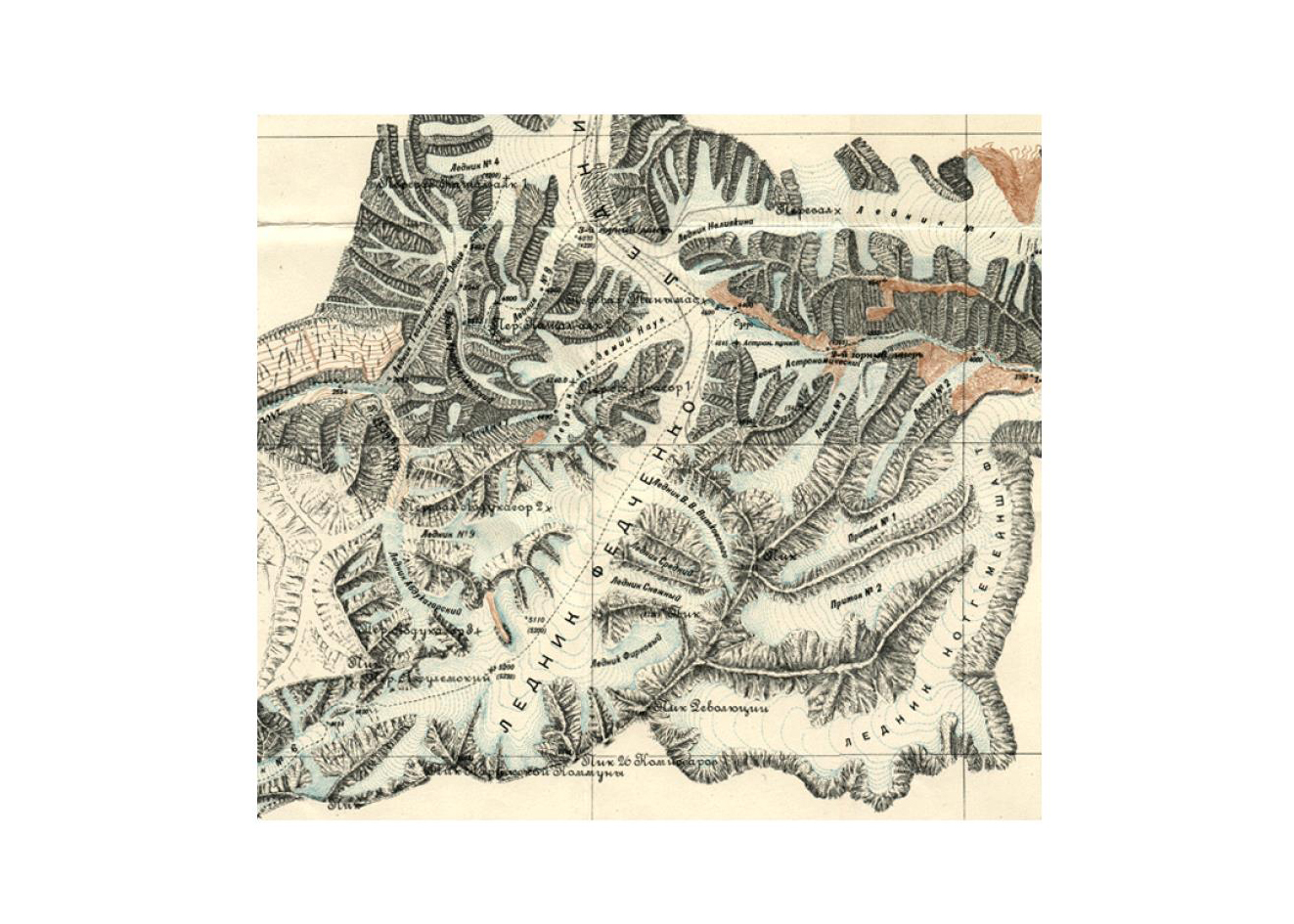

Map of the Notgemeinschaft Glacier

© aus Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Alai-Pamir-Expedition 1928 im Auftrage der Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft, 1932

Cooperation of this sort with Russian researchers was very unusual in the Stalinist era, and also captured public attention in Germany. In addition, it was considered the first major international research project in the expeditionary field – one only had to consider the broad scope of the research projects. The Russian team took charge of mineralogy, petrography and strategically important geodetic-astronomical tasks. The German expedition members concerned themselves with geology, surveying and mapping, glaciology and language research. Overall leadership was assumed by the Director of the Council of People's Commissars, Nikolai Petrovich Gorbunov, and organisational leadership by Willi R. Rickmers, who had already led a smaller German Pamir expedition in 1913. Including porters, interpreters and other helpers, the expedition comprised 65 men, 160 horses and 60 camels.

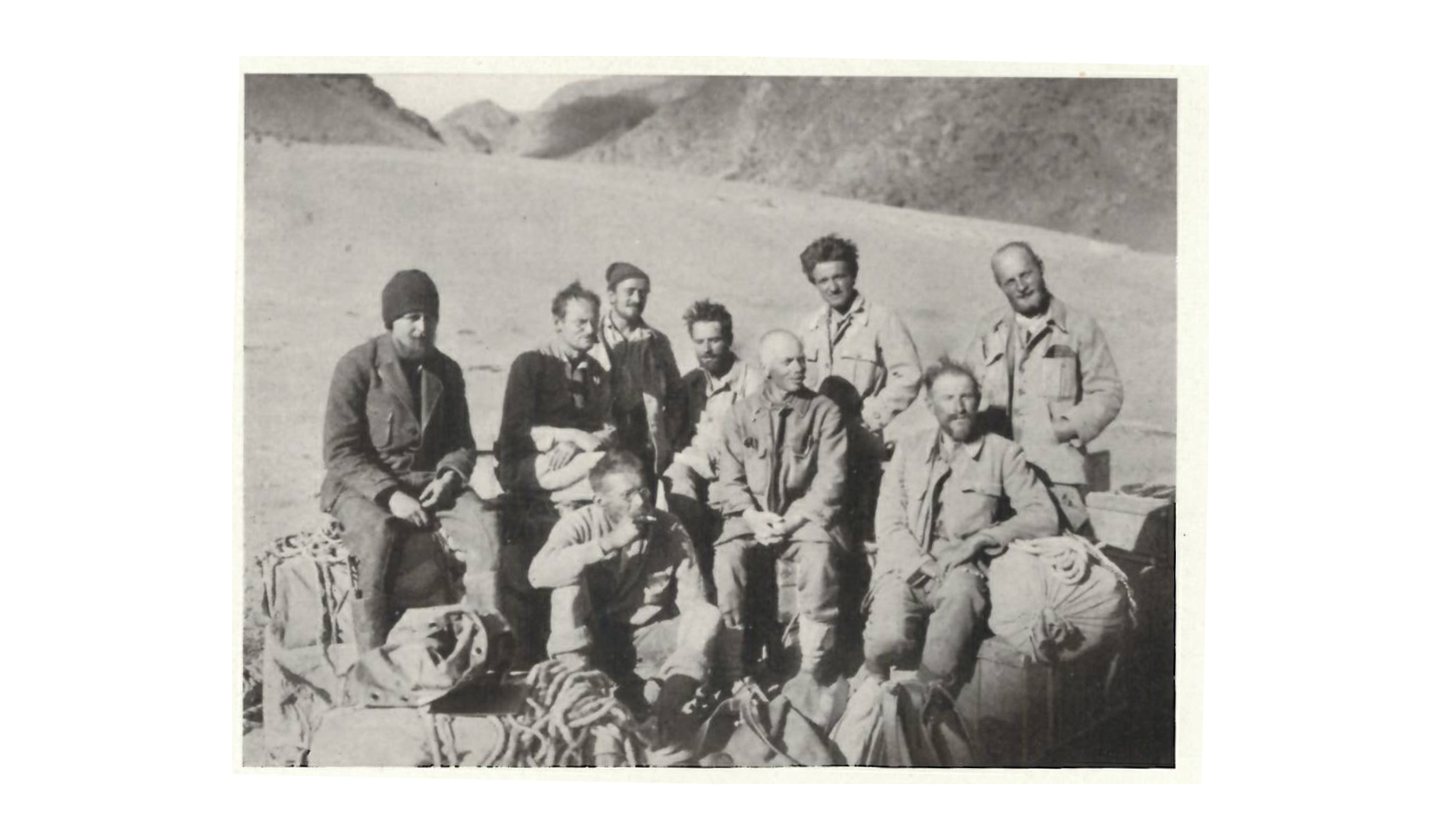

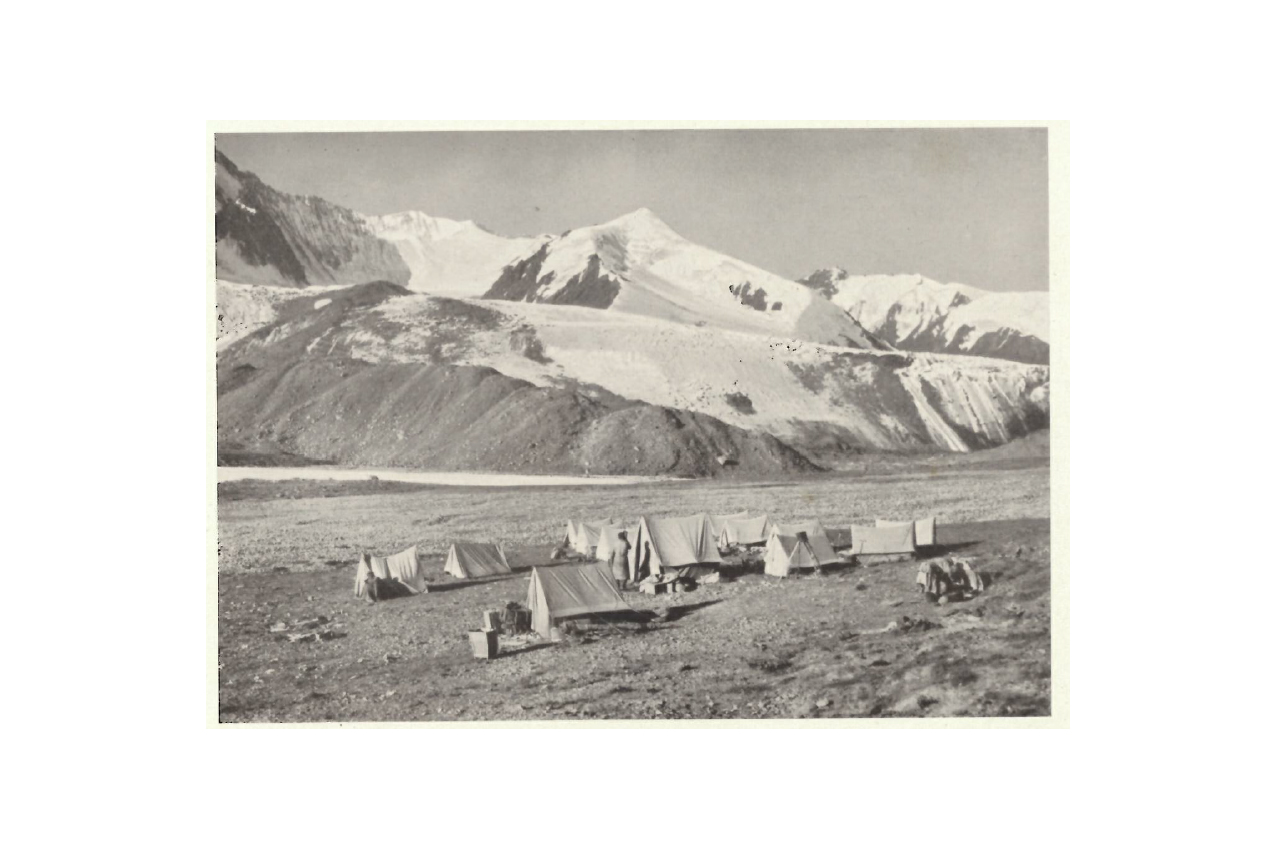

In the Kusguntokai camp

© aus der Zeitschrift des Deutschen und Österreichischen Alpenvereins, Band 60, 1929

The findings of the expedition were considered remarkable and were published in five volumes of text and a volume of maps. Four hundred photogrammetric images allowed the region to be recorded cartographically, and the first survey of the 77-kilometre-long Fedchenko Glacier to be made. In addition, the first ascent was completed of a peak above 7,000m. It was named Pik Lenin during the expedition.

The second-largest previously unknown glacier was named “Notgemeinschaft Glacier” in honour of the Notgemeinschaft. This name was in common use up to its renaming as “Grum-Grzhimailo Glacier” in 1948, and was used in maps and illustrations. Naming glaciers and peaks after people or concepts was nothing unusual. It was even suggested during the expedition that another glacier be named after the President of the Notgemeinschaft, Schmidt-Ott. However, the two leaders of the expedition, Gorbunov and Rickmers, decided that no peaks or glaciers should be named after participants or other individuals involved.

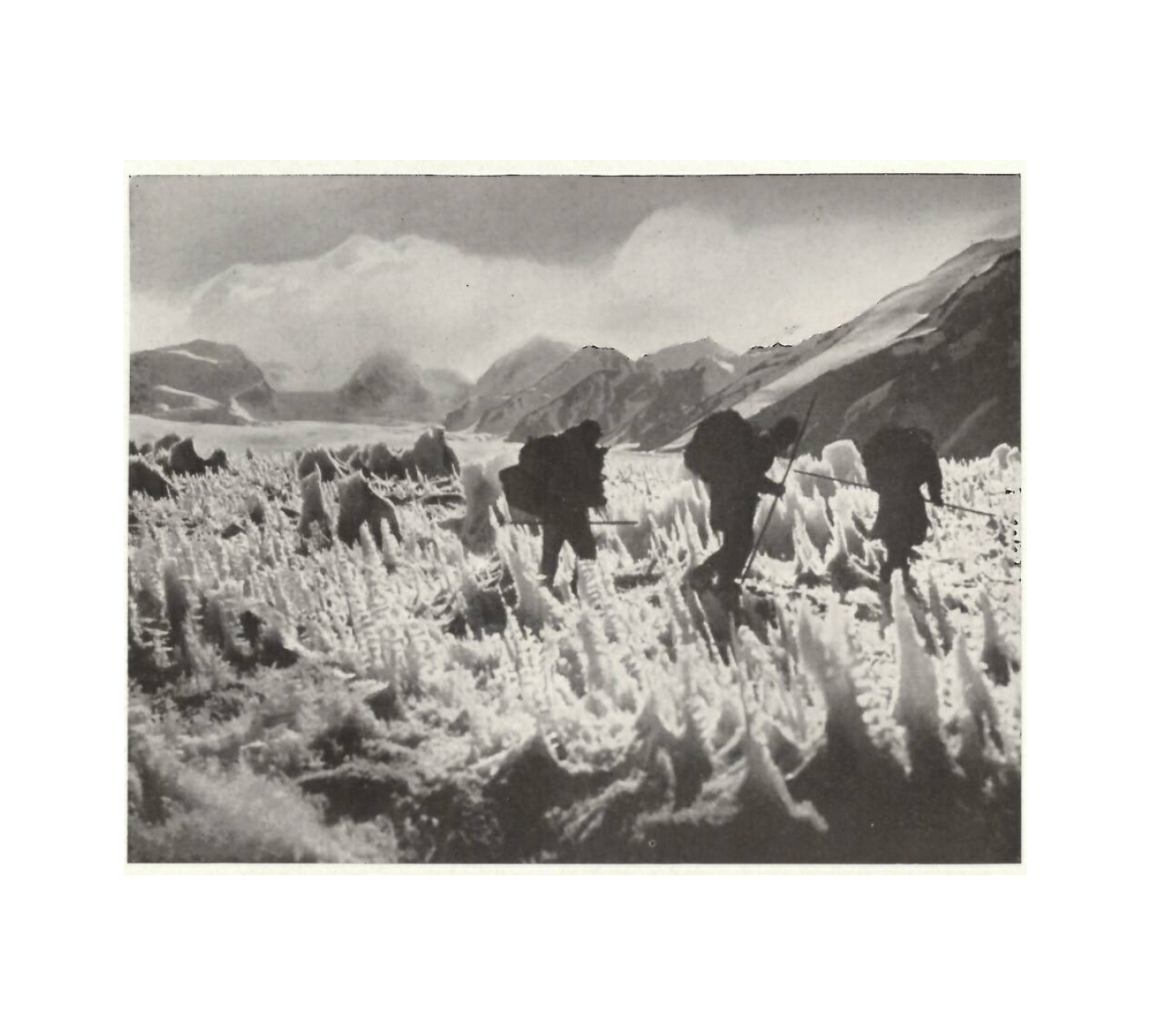

Four mountaineers also took part in the expedition at their own cost. In their report in the magazine of the German and Austrian Alpine Club they described the mountaineering excursions in detail and recorded them photographically, as in this photo:

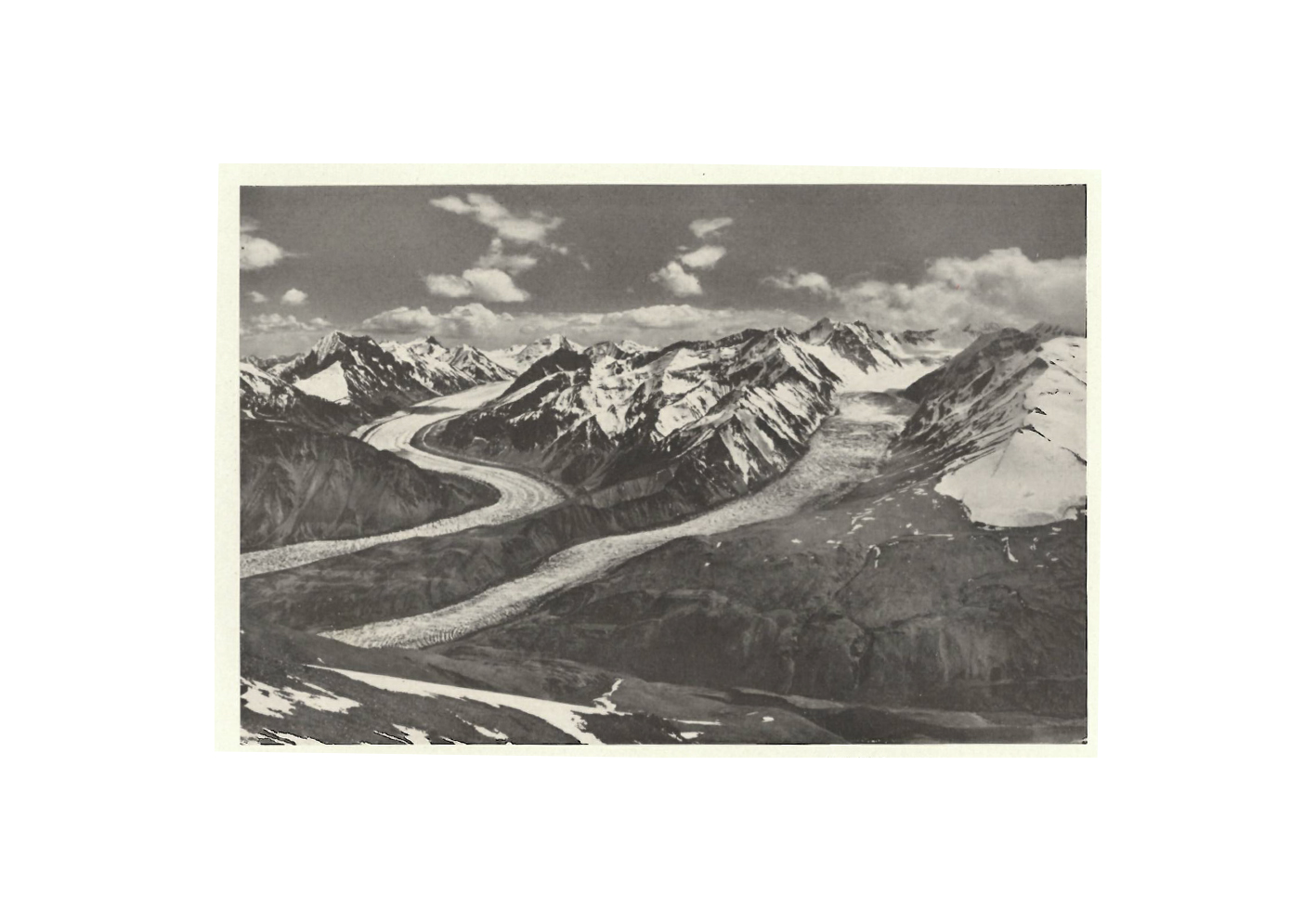

“Difficult progress on the Notgemeinschaft Glacier”

© aus der Zeitschrift des Deutschen und Österreichischen Alpenvereins, Band 60, 1929

Cooperation between the mountaineers and the researchers worked very well; however, they could not resist a tongue-in-cheek remark about the scientists relating to their stay in the Fergana Valley, when expedition members had to wait for their luggage:

“Apart from that, we 4 mountaineers lazed around, while the men of science, with the possible exception of the indefatigable Reinig, busily pretended to be doing something.” The expedition also enjoyed a very good reputation in relation to the harmonious cooperation of its participants. Finally, here is the assessment of expedition leader W. R. Rückmer on the research journey:

“It is almost a law that large travelling parties never come off without a fight. But in this case a miracle was wrought, namely that around thirty men, both Russians and Germans, lived side by side in harmony for several months, even if a cathartic word may occasionally have been spoken.”

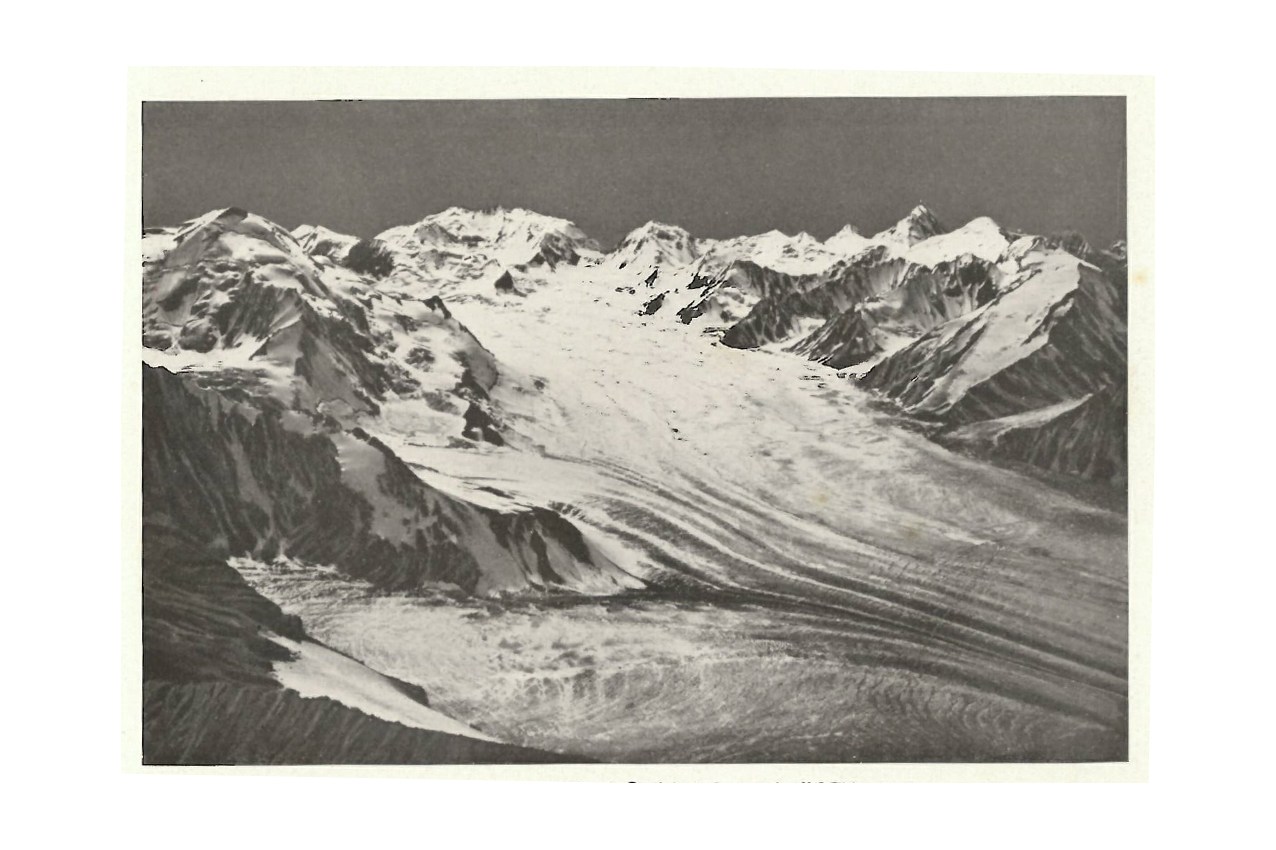

The Notgemeinschaft Glacier (L) and glacier Tanimas 2

© aus der Zeitschrift des Deutschen und Österreichischen Alpenvereins, Band 60, 1929

Further information

“GEPRIS Historisc(externer Link)” (in German only) is the comprehensive information portal provided by the DFG that makes the history of the DFG and of research between 1920 and 1945 publicly accessible.

Information on literatur(Download) used and sources.