An organisation conforms

- The Notgemeinschaft under National Socialis(externer Link)

- National Socialists take power in 193(externer Link)

- Self-mobilisation of research (1933 to 1934(externer Link)

- Change of power at the top of the German Research Foundation (1934) – stripping of executive bodies’ powe(externer Link)

- The presidency of Johannes Stark (1934 to 1936(externer Link)

- In the service of the NS regime (1936 to 1939(externer Link)

- During the war (1939 to 1945(externer Link)

The Notgemeinschaft under National Socialism

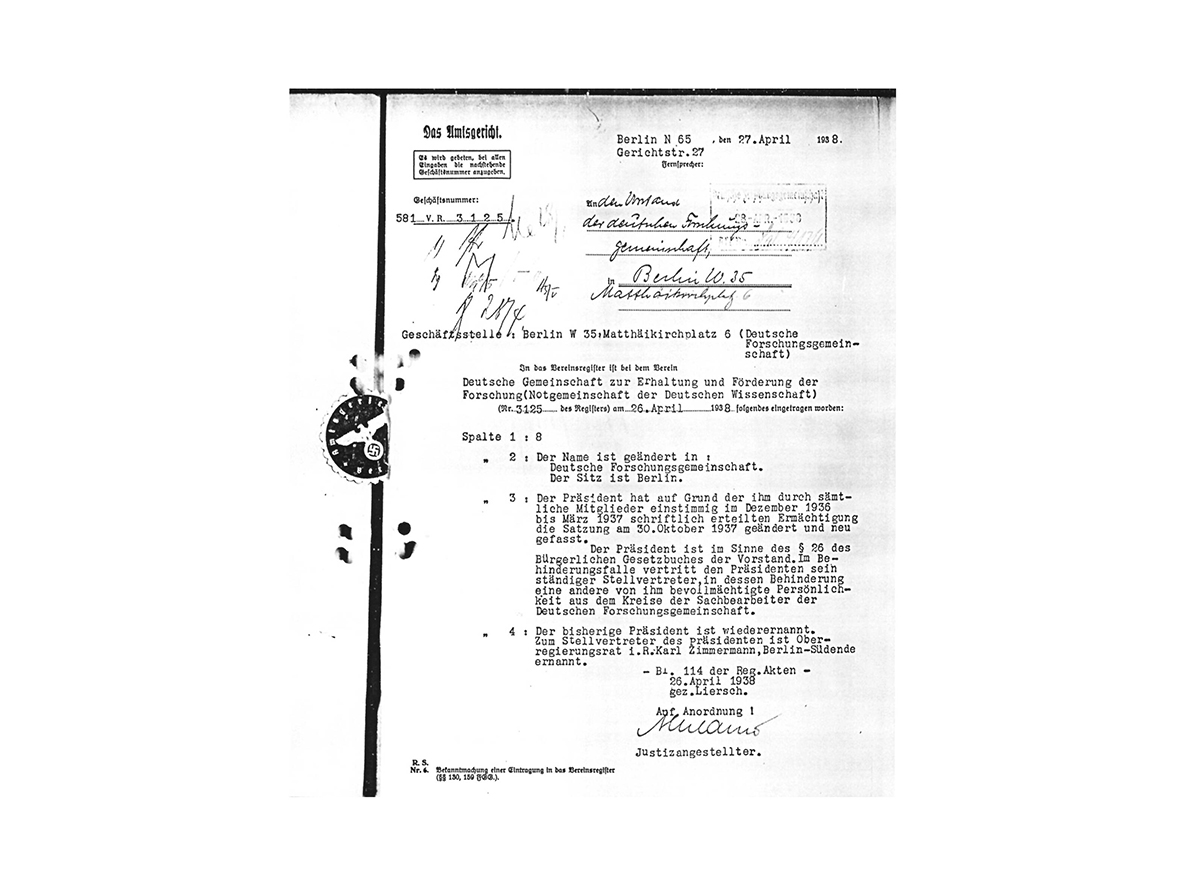

Extract from the association register extract dated 27 April 1938

© Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 73/14168, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

The Notgemeinschaft conformed to the requirements of the NS regime without much resistance: it surrendered its self-governing structures in favour of an autocratic Führer principle, and from 1937 it increasingly focused its work on funding research on war-related topics.

National Socialists take power in 1933

The National Socialists had no clear concepts for scientific and research policy after they took power in 1933. Hitler was not interested in this policy area, and seldom intervened in decision-making in relation to science and research. Over time, two different scientific policy institutions emerged. Their respective competencies were never clearly differentiated, however, and their procedures were characterised by personal power struggles.

Even if consistent university and research policies were almost impossible due to the bureaucratic chaos that existed in the academic domain, all National Socialist stakeholders still wanted to restructure the existing establishments along National Socialist principles:

- Staffing policies that focussed on “race” and political convictions as well as scientific and scholarly achievements

- The elimination of democratic structures

- The restriction of topics for science and scholarship to research on autarchy, armament, ethnology, race and health

The German Research Foundation conformed to this dictum in its management structure and funding policy, sometimes voluntarily in “pre-emptive obedience,” sometimes due to pressure from the state and those wielding its power.

It was characteristic of the relationship between the state and science that “scientists mobilised resources from the political sphere for their own purposes just as much as politicians used scientists and their resources for their own purposes” (Mitchell Ash, Science and Politics as Resources for Each Other, 2002, p. 33). Many scientists, scientific institutions and universities willingly used their expertise and infrastructure to impose NS doctrine for their own benefit. The state, in its turn, used science to justify its race ideology and the political implementation thereof.

Reorientation after 1933 occurred quickly and seamlessly – partly because it was not perceived as a “break with the system,” but rather as a continuation of developments dating back to the Weimar Republic, or even as far back as the Kaiser's reign.

The developments became evident in the successive stages of the German Research Foundation’s self-instrumentalisation from 1933 to 1945.

Self-mobilisation of research (1933 to 1934)

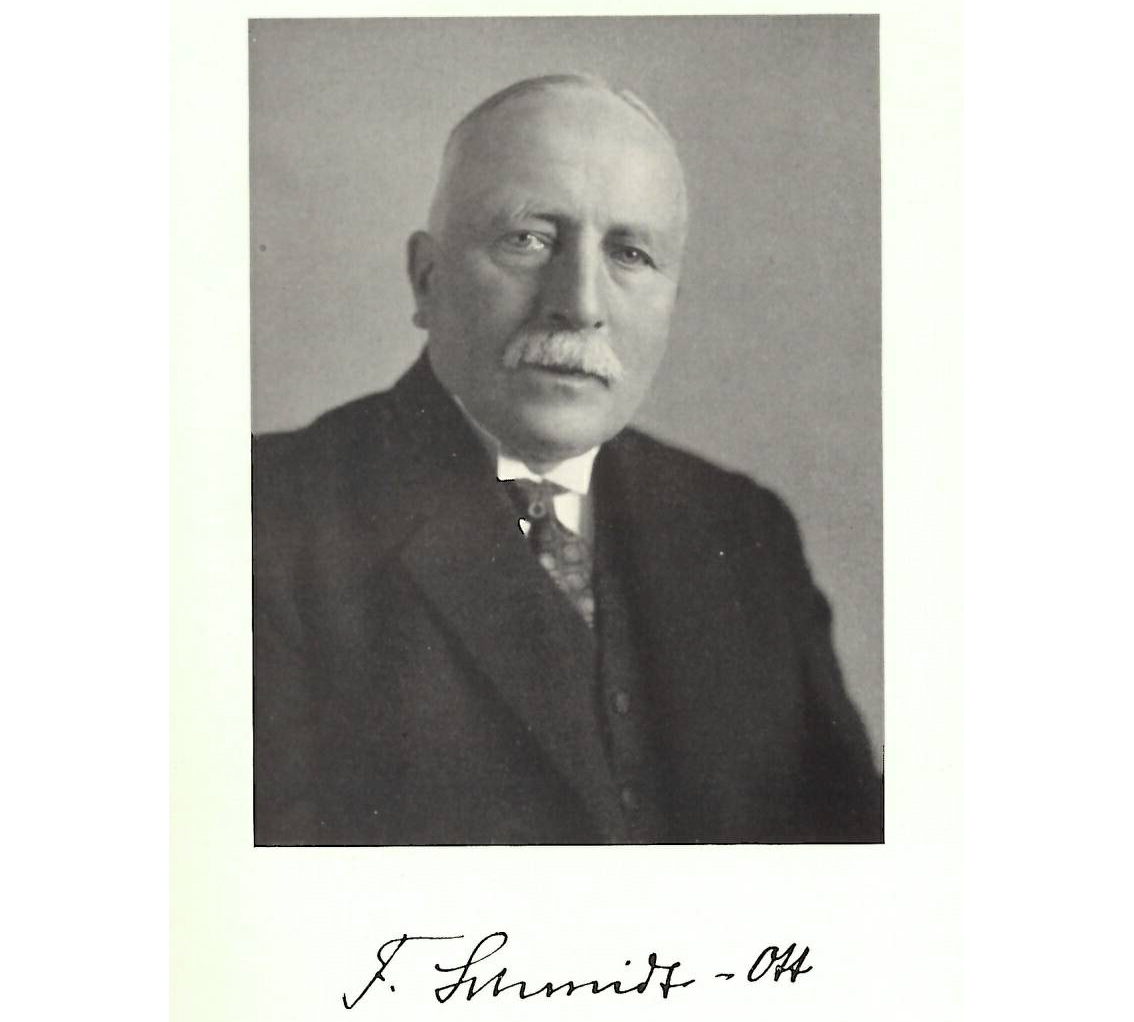

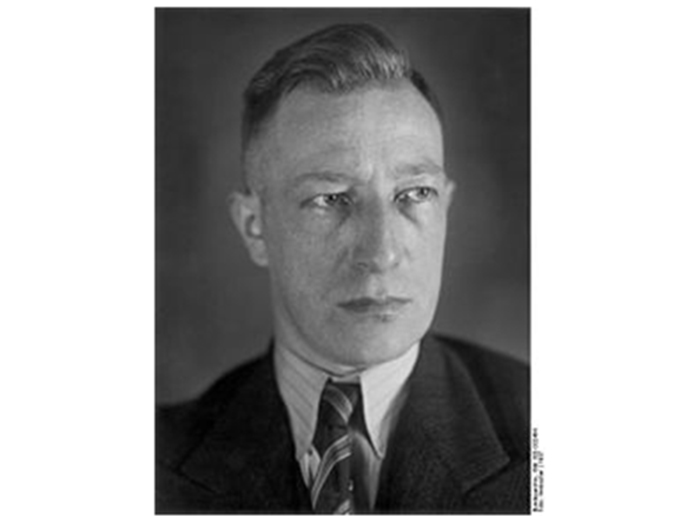

Friedrich Schmidt-Ott, President of the Notgemeinschaft from 1920 to 1934

© aus Schmidt-Ott, Erlebtes und Erstrebtes 1860-1950, 1952

The years 1933 and 1934 were primarily characterised by the compliance of the Notgemeinschaft with the new regime, driven by President Schmidt-Ott in particular.

Friedrich Schmidt-Ott, born in 1860, was active in numerous areas of scientific and cultural policy during the Kaiser's reign, and was the Prussian Education Minister from 1917 until November 1918. Along with Adolf von Harnack and Fritz Haber, he was the founding father of the Notgemeinschaft and, through great dedication, managed to avert the disbandment of the fledgling Notgemeinschaft in the difficult early years of inflation. It was thanks also to his involvement that the Notgemeinschaft was able to establish itself in extremely difficult economic times as a new form of research funding and a “solid pillar in the German research landscape”. Unlike competing foundations, the Notgemeinschaft supported all areas of science and the humanities, and all researchers could obtain their own financial resources for their projects after a successful review process, which was carried out as an open procedure by an elected committee. This enabled younger researchers, in particular, to research in larger institutes with many hierarchical structures.

The executive bodies and in particular founding President Friedrich Schmidt-Ott attempted to keep the Notgemeinschaft as an association under the NS regime. The price they paid for this was the loss of their self-governing structure. The Notgemeinschaft, with its system of diversity and as a largely self-governing organisation, fundamentally clashed with NS interests and – like many other institutions with democratic structures – had to accede to an autocratic new form of research funding vested with the “Führer principle” and obedient to the NS regime. In the months of March and April in 1933, the Reich Ministry responsible for the Notgemeinschaft, and later the Ministry of Science and Research, attempted to absorb the Notgemeinschaft or at least to strip it of power and to appoint servile National Socialists at the top.

Such considerations and plans naturally also affected Friedrich Schmidt-Ott and the executive bodies of the Notgemeinschaft. The latter dissolved themselves, giving in to pressure from the National Socialists, within a few days.

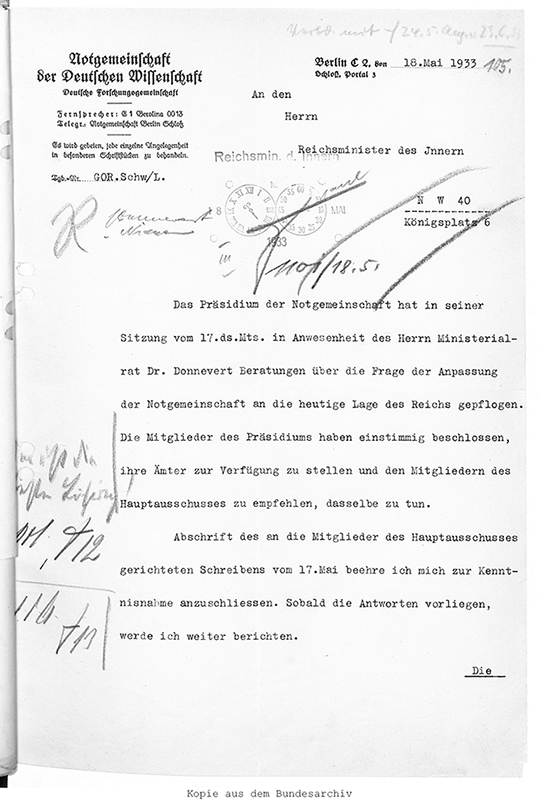

The Executive Committee’s letter of resignation dated 18 May 1933

© Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 1501/126769-c, Blatt 105, Notgemeinschaft

On 17 May 1933 the Executive Committee resolved to resign “as part of the adjustment of the Notgemeinschaft to the current situation of the Reich” and recommended to the members of the Joint Committee that they “do the same”. A new election was supposed to be undertaken by a General Assembly to be convened on 17 June 1933.

The Joint Committee abided by the recommendation and likewise resigned. The Joint Committee was to be newly constituted in January 1935. However, a ministerial directive dissolved the meeting. Under Rudolf Mentzel’s presidency, the Joint Committee was subsequently completely abolished from 1936.

At the instruction of the Reich Ministry of the Interior, the General Assembly called for 17 June 1933 was “postponed for an indefinite period” on 15 June 1933. The last General Assembly before 1949 met on 10 November 1934 in Hannover.

At the request of Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick, at first Friedrich Schmidt-Ott was able to continue to direct the affairs of the Notgemeinschaft provisionally.

Fritz Haber had already resigned his office as member of the Executive Committee of the Notgemeinschaft on 12 May 1933 – in view of the “Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums" (Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service) of 7 April, which transferred “non-Aryan” public servants into immediate retirement. Although Fritz Haber would have been exempted from the provision due to his military standing in the war, he considered the impending dismissals of his institute's Jewish employees intolerable – especially given that he himself as the director of the institute would have had to pronounce them – and on 30 April he submitted his request to be released into retirement as the director of the KWI of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry and as a professor of the University of Berlin.

Fritz Haber's explanation of his resignation: the incompatibility of his work as a scientist with the conditions of National Socialism

© Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde: R 73/1, Blatt 175, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

In his letter of resignation to Friedrich Schmidt-Ott, he reminded the latter of their years of working together for the Notgemeinschaft, which he nevertheless saw as being shaped by Friedrich Schmidt-Ott’s autocratic leadership style.

“Of all the painful surprises of this violent new era, this is the most unexpected. In the democratic era in which the development of the Notgemeinschaft occurred, I was occasionally angry with you because I preferred the collegiate principle to the Führer principle which you represented. Your concept has been victorious in the Notgemeinschaft in this time past, and now, when it has become a guiding principle of the state, the public world is turning against you and doing away with your Excellency and me, who began together in accordance with your wishes, at the same time.”

It was Friedrich Schmidt-Ott, more than anyone, who signalled to the NS regime that the Notgemeinschaft was prepared to adapt to the “new era” and who geared its funding practices increasingly towards issues related to armaments and autocracy. In so doing, he demonstrated both his agreement, and that of the academic community, with the goals of the new regime.

Friedrich Schmidt-Ott underlined again and again the significance of the Notgemeinschaft for National Socialism – and hence his own importance as its president – by highlighting many years’ work on National Socialist topics even before 1933. For example, he stressed in a memorandum written on 14 June 1934 and entitled “Notgemeinschaft and Research Council”, that

"the fact that the Notgemeinschaft has also, for a number of years now, conferred regular and ample funding on the neglected fields of German prehistory, German ethnology, anthropological and racial investigation of the German Volk, together with border and Saar research, should not be allowed to go unmentioned.”

He wrote that the Notgemeinschaft,

“with its extensive establishments, [could also] perform valuable services to the military command for its secret activities”.

In a letter to the rectors of the Notgemeinschaft's member higher education institutions in November 1933, Friedrich Schmidt-Ott alluded to future core areas:

“research that is dedicated to race, Volkstum [national values] and the health of the German Volk”

The research community did not perceive the changes implemented after 1933 to be particularly significant. The authoritarian leadership style of Friedrich Schmidt-Ott, who regularly circumvented the executive bodies, was compatible with the National Socialists’ anti-democratic “Führer” principle. The thematic focus of the Notgemeinschaft corresponded to a basic consensus prevailing in society, even at the time of the Weimar Republic, that research was expected to make its contribution to Germany's rise as a major power. Friedrich Schmidt-Ott and other leading persons in science and scholarship had already demonstrated anti-Semitic tendencies before 1933.

In view of this situation, it is not surprising that neither the exclusion of Jewish researchers from research funding nor the dismissal of a Jewish employee of the Notgemeinschaft attracted attention, and that anti-Jewish measures were implemented even before the deadlines set by the state.

Change of power at the top of the German Research Foundation (1934) – stripping of executive bodies’ power

However, despite his copious attempts to conform, Friedrich Schmidt-Ott could not retain his position as President. To the National Socialists he was too much of a prominent representative of the old political system. From May 1933 he was only permitted to continue to direct affairs “provisionally”. Minister Bernhard Rust ended the delay in Friedrich Schmidt-Ott's severance, which had been due to changes in ministerial responsibilities, in summer 1934, and appointed Johannes Stark as the President of the Notgemeinschaft.

Friedrich Schmidt-Ott describes the circumstances of the handover in his biography “Erlebtes und Erstrebtes” (Experiences and Aspirations):

“In a meeting which I had thereupon with Minister Rust on 23 June [1934] he informed me that Hitler wished to see Herr Stark in my position. (...) In view of Herr Rust's message, I immediately declared my resignation, however. I had hardly arrived back in my office in the Schloss when Ministerial Director Vahlen together with Stark announced his imminent visit in order to take over business. For that reason I had to limit myself to a brief farewell to all members of the Notgemeinschaft.”

Friedrich Schmidt-Ott’s active involvement with science policy did not end with his resignation, however; at the end of 1935 he was elected Chair of the German Stifterverband (Donors’ Association) and took part in senate meetings of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. Upon the re-establishment of the Notgemeinschaft on 11 January 1949, Friedrich Schmidt-Ott was unanimously elected by the General Assembly as “Honorary President”.

In order to cover up Stark's appointment as President and thereby this obvious breach of the statutes, a retrospective vote was staged which was to be submitted in writing by the association members. Minister Rust informed the member institutions in a circular that a gathering was to be waived for “reasons of cost” and called upon the members to agree, in a hectographed declaration of consent, to the installation of Johannes Stark as president and to empower him to amend the statutes “in line with a closer affiliation of the association's objectives with the goals of the National Socialist government”.

The Prussian Academy of Sciences’ rejection of the election of Johannes Stark as President

© BBAW: PAW II-XIV-34, Blatt 53

It was a sign of the still incomplete take-over of research and scholarship by the National Socialists that only 47 of the 57 member organisations responded “positively” and four responses were never received, despite reminders. The President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, Max Planck, abstained from voting. The only higher education institution to reject Minister Rust’s proposal was the University of Munich; four of the five academies also withheld their consent. This included the Prussian Academy of Sciences, which did not sign the relevant form, but appended a hand-written rider: “because it sees the form as lacking the necessary organisational authority”. The Academy had resolved on this course of action in an extraordinary meeting on 23 July 1934, and informed the Ministry to this effect in a separate letter.

The Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities reacted similarly:

“Excellent as the achievements of Herr President Professor Dr. Johannes Stark are in his specialist field, he is relatively one-sided even in the field of physics. For this reason we cannot expect that he will possess the overview that is indispensable for the President of the Notgemeinschaft in the latter's extremely diverse duties and that his predecessor possessed to such an uncommonly high degree.”

The Reich Ministry of Science determined on 3 August 1934 that, according to the results of the voting, “the required confirmation of the election of President Stark [had] taken place” – a false statement, since according to the provisions of the Civil Code a unanimous vote is necessary for a written ballot. The register court nevertheless registered the new president in the association register on 14 August 1934.

The presidency of Johannes Stark (1934 to 1936)

Johannes Stark

As the President of the German Research Foundation from 1934 to 1936, Johannes Stark further expanded an autocratic leadership style. He had received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1919 and was a co-founder of “German Physics”, a movement that combined physics with racist views. He was an early supporter of the “Hitler movement” and boasted about the fact that he had provided Hitler with food during the latter's detention in Landsberg. In April 1933 he was appointed, against the advice of all the experts, as President of the Imperial Physical Technical Institute. Johannes Stark developed numerous activities that went beyond his office to reorganise the German research system and to restructure the Notgemeinschaft – preferably under his leadership.

Staffing changes in the head office occurred immediately after Johannes Stark's election as President: some of Schmidt-Ott's most important employees were dismissed and the library department was attached to the Prussian State Library. Johannes Stark was overburdened by his role as the head of the Imperial Physical Technical Institute and appeared in the head office of the Notgemeinschaft, which employed a total of 60 people, for only a few afternoons per week.

Similar to the practice at German universities, in which decision-making bodies were largely stripped of their powers and the elections of office-bearers were replaced by appointments, this “Führer principle” was introduced into the Notgemeinschaft under the presidency of Johannes Stark and continued under Rudolf Mentzel. Approvals for extensions of research fellowships were made orally, for example on the sidelines of conferences. All awards required the President's personal consent, and he reserved the right to make the sole decision. Friedrich Schmidt-Ott had, however, already practised an autocratic leadership style, given that the central self-governance bodies only had a quite restricted function under his presidency.

Within the head office, Johannes Stark conducted himself in a high-handed and self-important manner, answering the telephone with “President here!”. Numerous approvals for personnel and material resources were issued for the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (Imperial Physical Technical Institute), which Johannes Stark still headed. Preference was given to the natural sciences, and the humanities survived on the margins, and were restricted to ideologically relevant areas.

His hobby-horse was moor gold-mining – the attempt to extract gold from the Bavarian moors. However, the financial expense exceeded the mineral benefit many times over. This did not prevent Johannes Stark from putting a considerable portion of grant money into this research. As a proponent of “German Physics”, Johannes Stark rejected the newly emerging theoretical physics – with Werner Heisenberg and Albert Einstein as its proponents – and hampered modern physics. His one-sided prioritisation of experimental physics was evidenced by the fact that the Notgemeinschaft no longer funded any theoretical projects.

Stark's letter of resignation dated 26 November 1936

© BBAW PAW II-XIV-34, Blatt 88

The Reich Ministry of Science wanted to integrate the German Research Foundation into an organisational structure dependent on the Ministry. These aspirations ran counter to the ambitious and high-handed conduct of Johannes Stark, so that rivalry inevitably arose between him and the Ministry.

His power struggles with the Ministry prevented Johannes Stark from being able to secure a better financial position for the Notgemeinschaft. After he had made excessive demands totalling 19 million Reichsmarks for 1935/1936, only just under 4.4 million Reichsmarks were allocated for 1935, and for 1936 a mere two million. The statements of accounts that were still published annually under Friedrich Schmidt-Ott did not exist under Stark's presidency for the years 1934-1936.

The power struggles came to a head when Johannes Stark appointed the members of the Joint Committee without consultation with the Reich Ministry of Science – National Socialists but also renowned researchers such as Max Planck and Ferdinand Sauerbruch were among them – and invited the Joint Committee to an inauguration. This event was a fiasco for the President of the Notgemeinschaft, since he had to end the session after his introductory presentation because of an express despatch that arrived from the Ministry.

Furthermore, Johannes Stark wrongly believed himself to be secure in the favour of the “Führer”, but the latter kept out of the disputes over influence on research policy. For another thing, the political influence of Johannes Stark's mentor in the NS hierarchy, Alfred Rosenberg, was gradually waning. Johannes Stark's management of his office, in particular his moor gold research, also appeared so parlous and his support from powerful party colleagues so lacking, that he could no longer retain his office.

On 14 November 1936, Johannes Stark was dismissed by Minister Bernhard Rust after his resignation request, and Rudolf Mentzel was appointed provisional head of the Research Foundation. After the end of the war Johannes Stark was brought before a court and sentenced to four years in a labour camp. In 1949 this sentence was reduced to a monetary fine in an appeal process.

In the service of the NS regime (1936 to 1939)

Rudolf Mentzel

© Wikipedia, „Rudolf Mentzel“

Even as a student, the chemist Rudolf Mentzel was a member of the NSDAP, the SA and later a member of the SS. In 1933 he habilitated with a thesis on chemical weapons. After his appointment to the higher education division of the science ministry in 1934, he rose to the position of Director of the Ministry and was involved in the feud between the Ministry and President Stark. Rudolf Mentzel took over the presidency at the age of 36. The style of the head office, which comprised 60 employees at the time, changed fundamentally. He conducted himself in a pointedly comradely fashion, and did away with grandeur and distance.

Rudolf Mentzel was preparing for a completely new order, unimpressed by the self-image and practice of the German Research Foundation. Appointed by Minister Rust as the provisional head of the Notgemeinschaft, he attempted – like his predecessor Johannes Stark – to sanction his election retrospectively. In his case, too, there were members (the universities of Freiburg and Münster, the Technical University of Karlsruhe, the Academies of Göttingen and Munich and also the Society of German Researchers and Physicians) which contested Rudolf Mentzel's installation and only gave in under pressure. All the declarations of consent were finally sent to the Amtsgericht (local court) of Berlin in January 1937, and the association register entered the amendments accordingly in 1938.

Amendment of the statutes in 1937/1938

Rudolf Mentzel amended the statutes to reflect reality: the expert committees, which had been meaningless since Stark’s presidency, and the Joint Committee, which had not existed since the spring of 1933, were no longer even mentioned in the statutes. In line with the Führer principle, executive bodies were replaced with a leader: the President “determines the utilisation of the available financial resources after hearing from appropriate expert staff”. The role of reviewers was merely to support the President in his determination on the allocation of research funding. (Sections 5 and 7)

The General Assembly continued to exist, since this was a mandatory requirement for the formation of an association, and an association without members was unthinkable even under National Socialism. The form of an association was retained in order to suggest a certain degree of autonomy. However, the General Assembly no longer had any decision-making powers under the new statutes. It was stripped of the right to elect the President, who was instead “appointed and removed by the Reich Minister for Science, Education and Volksbildung [national culture]”. (Section 4) The function of the General Assembly was reduced to ”providing suggestions in relation to the internal and external mode of operation of the German Research Foundation”. (Section 8)

Gradually, the German Research Foundation lost its self-governing status in successive stages; the General Assembly was destined not to convene again until its re-establishment in 1949.

The cover page of the Festschrift (commemorative publication) on the establishment of the Reichsforschungsrat

The formation of the Reichsforschungsrat (Reich Research Council)

On 16 March 1937, the Reichsforschungsrat (RFR) was founded as a new coordinating body. It was the outcome of agreements between the Reich Ministry of Education and the Heereswaffenamt (Army Ordnance Office) and was intended to focus research on the objectives of the Wehrmacht and the Four Year Plan. The German Research Foundation therefore had to cede the funding areas that could serve the expansionist and socio-biological objectives of National Socialism – the natural, agrarian and engineering sciences – to the RFR.

For these disciplines it was important to harness the “right” applicants and projects for the purposes of war. To this end, the expert committees in those areas were dissolved, and replaced by 13 (later 16) so-called Fachsparten (expert departments), the heads of which were furnished with enormous power. It was within their own discretion to obtain reviews or not; ultimately their decision on all proposals was final. Furthermore, they were no longer appointed by the research community, but rather by the Reich Minister of Education. This meant that the expert departments decided matters on which 159 elected members had previously deliberated in the central bodies. The principle of taking pluralistic opinions into account in the process of reviewing funding proposals was abolished.

In addition, the expert department heads were expected to expand cooperative arrangements with institutions of the regime, army and industry, and establish research groups. They established working groups in which representatives from government, industry and the military took part alongside researchers. Cooperation arrangements were entered into with KWG institutes, the Armaments Ministry and academies. For example, the head of the Expert Division for Electrical Engineering, Erwin Max, took part in a naval congress on the topic of “Oscillation research for the U-boat war” and visited facilities of the armaments industry. The RFR mainly supported projects of direct relevance to the military, for example infrared measurement techniques in the service of air defence, camouflage of U-boats, development of Panzer motors and the investigation of “hardened captured weapons of outstanding strength”.

The RFR not only funded projects by applicants, but was also authorised to commission research itself. The abolition of the expert committees and the reduction to individual heads of expert divisions did not necessarily signify a break with the decision-making culture of the German Research Foundation. Even in the Weimar Republic, in most cases only one reviewer from the relevant expert committee had made the decision, to which the chairman of the committee generally acceded.

The German Research Foundation had to restrict itself to those areas “with which the Reichsforschungsrat does not concern itself, for example research on the Auslandsdeutsche (Germans living abroad) and Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) (and) research in the humanities.” Since the RFR did not have its own budget and was not a legal entity, the German Research Foundation took over the administration and issuing of funding decisions on behalf of the RFR.

The President of the German Research Foundation, Rudolf Mentzel, continued to occupy a central position in resource allocation as the “Director of the Managing Advisory Council of the Reichsforschungsrat”. General Karl Becker, Dean of the Military Technology Faculty at TH Berlin and the designated head of the Army Ordnance Office, was appointed President of the RFR.

DFG President Rudolf Mentzel – shown here in 1941 at the presentation of the Atlas of Central Asia funded by the DFG – habilitated as a chemist at the University of Greifswald in 1933 without the faculty having been permitted to see his habilitation dissertation. The thesis was deemed confidential due to its topic – the military use of poison gases

© Aus: Heinemann et.al. (2005): Wissenschaft Planung Vertreibung. Der Generalplan Ost der Nationalsozialisten. Katalog der Ausstellung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft, S. 12

The increasing focus on war-related research topics and the close links between war agencies and the RFR was not new, however, and was not a phenomenon specific to the National Socialist regime. This phenomenon had already been witnessed before and during the First World War. Researchers with fundamentally nationalistic convictions were prepared – especially after the 1918 defeat – to allow themselves to be mobilised for the goals of National Socialism.

During the war (1939 to 1945)

Through a change in the Executive Committee in May 1939, almost all important institutions relating to the four elements – government, industry, the military, research – were represented on the Reichsforschungsrat. In addition, the Notgemeinschaft’s range of duties expanded in October 1939 with the incorporation of three new expert divisions – transport, organic chemistry, and “Bevölkerungspolitik, Erbbiologie und Rassenpflege” (population policy, hereditary biology and racial hygiene).

A “Wartime Industry Unit” was set up in the German Research Foundation soon after the beginning of the war, which allocated priorities and codes to the researchers. These categories were a direct indication of whether research projects were considered particularly important, only of limited importance or not at all important. The researchers received materials depending on their priority after consultation with the heads of the expert divisions. For funding recipients who were drafted, the German Research Foundation determined precisely whether and to what extent they were permitted to continue to receive research grants and fellowships during their war service.

In March 1940 the President of the RFR, Karl Becker, took his own life – the crisis in the armaments industry, disputes over jurisdiction and family problems were the likely reasons for his suicide. His successor was Reich Minister Bernhard Rust, who appointed himself to the position. When the military situation deteriorated in 1942, criticism of the RFR was voiced in relation to the mobilisation of war-related research. Power struggles broke out, which Reich Marshal Hermann Göring ultimately managed to decide in his own favour in the summer of 1942, assuming the presidency following Rust's resignation.

Since the start of the war, the Reichsforschungsrat and the German Research Foundation had been championing their project funding in the field of autarchy and armament research, especially in those areas that were directly connected to National Socialist policies of invasion.

The funding of the General Plan East by the Reichsforschungsrat is an example of the close interconnection between research and expansionist policies as well as the connection between the DFG and the NS agencies relevant to the war. In 1939 Konrad Meyer, who had been head of the expert division for “Agricultural Sciences and General Biology” in the Reichsforschungsrat since 1937, advanced to the position of responsible chief planner for SS resettlement policies through his appointment as the head of the “Planning Department of the Reich Commission for the Strengthening of German Volkstum” (RKF). In this function, he was responsible for the development of the General Plan East, drafted in 1941/1942, which envisaged the ethnic homogenisation of large areas of Eastern Europe through the relocation of the local population and settlement of Germans. In his dual role, Konrad Meyer acted as Project Coordinator. He received a part of the annual allocation from the Reich Commissioner for "Planning studies for the strengthening of German Volkstum" directly; the remainder was available for individual proposals by researchers to the Reichsforschungsrat, which Konrad Meyer examined himself and on which he decided as the head of the expert division. In this way the German Research Foundation – by authorising payments – funded projects that dealt, for example, with “Tasks for the strengthening of German Volkstum in the new settlement areas,” or carried out investigations on “Volksbiologische (ethnobiological) and volksgemeinschaftliche (ethno-communal) prerequisites for rural development in the new German east”. The DFG has dedicated an exhibition to the critical reappraisal of the “General Plan East”. The exhibition was created as part of a research project on the history of the DFG, and has been on display as a travelling exhibition since 2006.

A number of new government agencies were created in 1944 in frantic efforts to improve the central coordination of critical war research – with the result that the organisational structure of the Reichsforschungsrat became even more confusing: the newly established “Wehrforschungs-Gemeinschaft” (Defence Research Foundation) was allotted the task of eliminating difficulties in procurement of materials and displacement space/transport space. All the heads of the RFR’s expert divisions and the appointed heads of the “field offices” of higher education institutions were part of the Wehrforschungs-Gemeinschaft.

In March 1945, hectographed letters were sent to funding recipients with the note that “At present a considerable slowing in deposit transactions for the funds [has] arisen”. These difficulties – and this is where the unrealistic hope of an ultimate victory is expressed – could well be “resolved within the foreseeable future”. Hence the letter concluded with a blank approval of an amount that was not derived from a direct proposal, but mostly corresponded to three monthly instalments.

The operations of the head office of the German Research Foundation continued until the capture of Berlin by the Soviet Army at the beginning of May 1945, as the building in Grunewaldstraße was not hit by bombs. Rudolf Mentzel distributed a quarter-year's salary and food packages to all employees shortly before the end of the war and then withdrew to Schleswig-Holstein with the Reich Minister for Education Bernhard Rust and the minister's senior staff. There Bernhard Rust took his own life and Rudolf Mentzel was taken prisoner by the Americans. A two-year internment and subsequent tribunal proceedings followed, in which he was sentenced to two years in prison, mainly due to his membership of the SS, which were however deemed to have been served by the period of internment. After a vain attempt to establish a laboratory with the support of the Max Planck Society, Rudolf Mentzel finally took up a position in industry.

The Notgemeinschaft building was occupied by American troops, and the head office had to move to Kommandantenstraße in Berlin-Lichterfelde. Karl Griewank, Consultant on the Humanities, represented the German Research Foundation as its chief executive officer, and wound up its affairs and finances in a proper fashion.

Further information

“GEPRIS Historisc(externer Link)” (in German only) is the comprehensive information portal provided by the DFG that makes the history of the DFG and of research between 1920 and 1945 publicly accessible.

Information on literatur(Download) used and sources.