“Been in America”: Interviews with German researchers in the USA and Canada

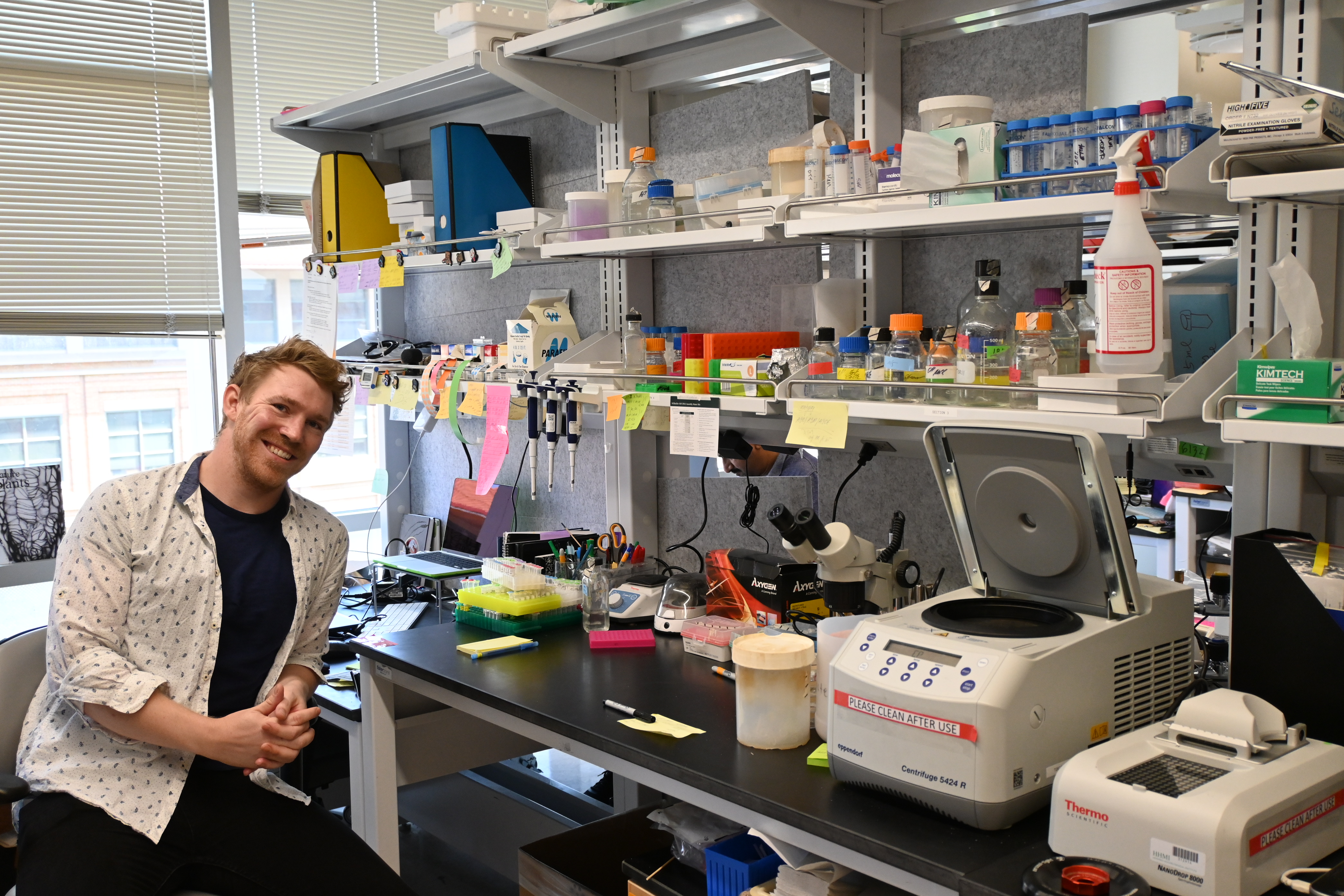

Dr. Arvid Herrmann

© Privat

(10/31/22) Through its Walter Benjamin Fellowship, the DFG supports early-career academics by funding an independent research project abroad and, as of 2019, in Germany, too. Many of these scholarships are awarded for research in the USA and Canada. In many disciplines, especially the life sciences, there is a belief that it is helpful for a career in research to have “been to America.” In this series of talks, we aim to give you an impression of the range of DFG funding recipients. In this edition we take a look at who is behind funding number HE 8812.

DFG: Dr. Herrmann, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to the DFG’s North American office. In your curriculum vitae it says you were born in Lebach in Saarland and you attended upper secondary school in Calw in Swabia; your name has a touch of Nordic mythology, but your accent is more suggestive of the lower Rhineland. Do enlighten us.

Arvid Herrmann (AH): I’ll be very glad to, but first of all thank you very much for the fellowship and for this opportunity to reflect on myself and my career – something that often tends to get lost in everyday life. I was born the eldest of three children in a household run by a library assistant (my mother), while a former sergeant major of the German Federal Armed Forces (my father) kept things in order. Part of my family comes from the Rhineland, and even though I don’t actually speak the dialect, I do tend to adapt very quickly to the person I’m talking to. My first name actually does have its roots in Old Norse and means something like strong eagle or eagle in the storm. My brothers’ names are Cedric and Gerrit, so my parents were obviously keen on Nordic-sounding names and probably didn’t want to go too far down the alphabet in their choices. Names like that are easier to call out on the playground, too.

DFG: You hold a doctorate in plant biology. When and how did you decide to opt for this field?

AH: As a child I was always fascinated by research, mainly dinosaurs and excavations. So I wanted to be a dinosaur researcher, with a touch of Indiana Jones. The fascination for research and science continued at upper secondary school, although I wasn’t necessarily always an A student in non-scientific subjects. Although my parents aren’t academics and both my brothers have pursued careers outside academia, my father was keen for me to study medicine in the armed forces. Unfortunately, I opted for a different path from what he would have wanted for me because I had my heart set on biology, and I knew at the time that I wanted to do a doctorate in the subject. Having been a conscientious objector at the age of 18, from my father’s point of view this was actually the second time his eldest son failed to fall into line. To top it all off, I also “came out of the closet” in the following years, which was something my family had to learn to deal with. All this might sound like the latest coming-of-age drama to be aired by a streaming provider of your choice, but fortunately it wasn’t; my parents are actually very understanding and have always supported me. They both came to visit me frequently during the first years of my biology studies in Tübingen too, regularly filling my fridge. But initially neither of them – even less than myself – were able to imagine that someone with a university degree not related to a well-established profession such as that of a lawyer, doctor or teacher could be anything other than penniless. The only thing that was important to them was that I had a plan – and preferably one with a backup. My parents simply didn’t want me to end up broke.

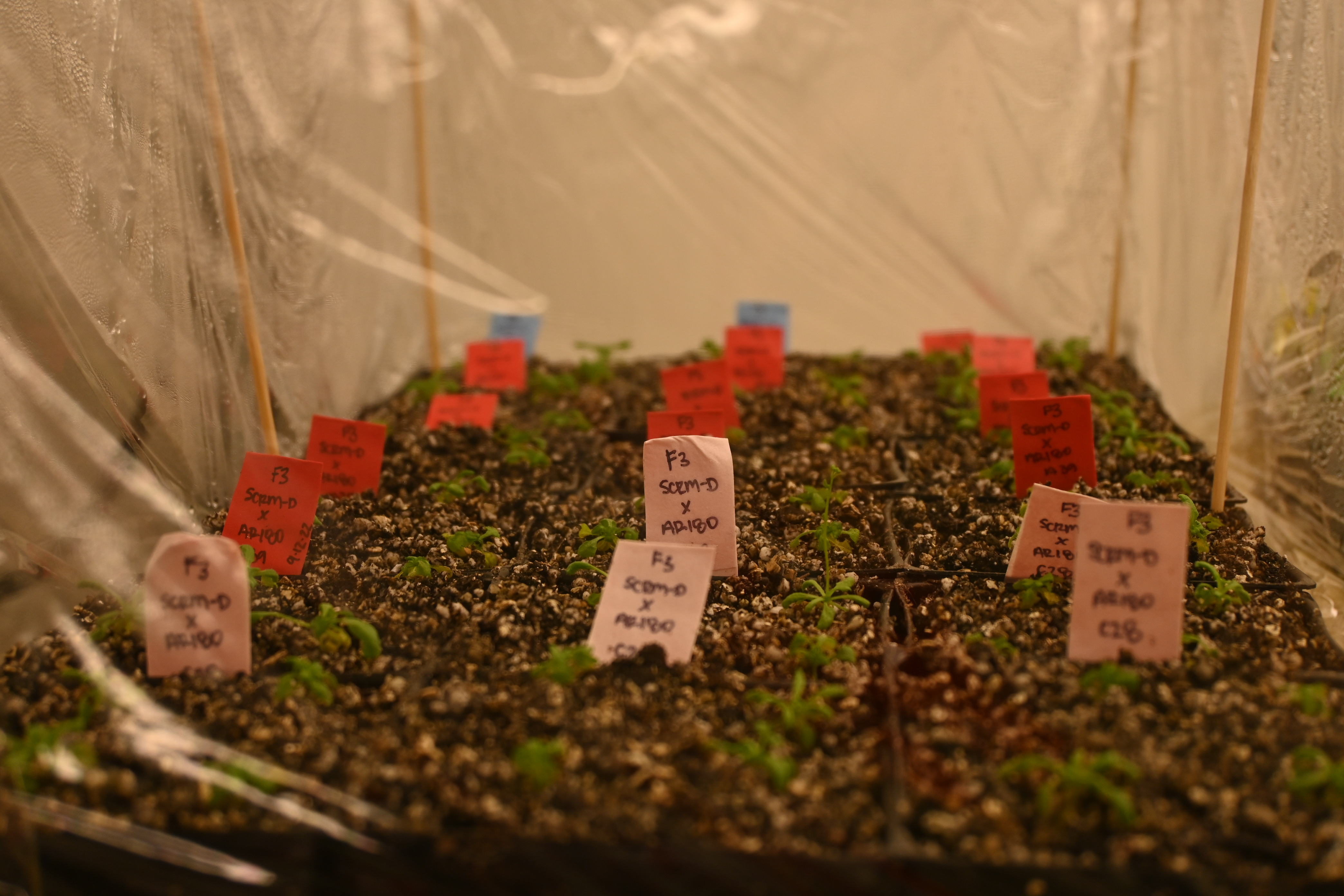

Arabidopsis in the plant room

© Privat

DFG: What about you yourself? Didn’t you have any worries in this regard? Apart from being interested in going to university to do research, did you have any inclination towards other “penniless” pursuits such as music, art, or acting?

AH: I continued the inclination towards penniless pursuits in the theatre group Szenario at the University of Tübingen. Among other things, they cast me in the role of Lord Henry Wotton in Dorian Gray, and everyone said I was typecast. I’m not sure that was a compliment: Lord Henry is an explosive mix of intellectual brilliance and arrogance, and I’m not quite sure which aspect I was able to convey more “naturally.” I’ll leave that judgement call to others [laughs]. We also had another play by Oscar Wilde in our repertoire, The Importance of Being Earnest. That’s actually an awful comedy of mistaken identity, but it does have nice roles, such as that of a priest who has a crush on a governess. It was a lot of fun and I had a great time.

DFG: At the University of Tübingen, apart from your theatrical career, you completed your doctorate at the Center for Plant Molecular Biology (ZMBP) with a thesis on cell division mechanisms in Arabidopsis thaliana, a plant that fascinated you ever since your undergraduate studies. Isn’t that rather too narrow a subject for an academic career?

AH: You mean because people don’t eat thale cress and have never heard of it? Actually no, it’s a very central model organism for plant biology – comparable with Drosophila or the zebrafish -- with the essential difference that I don’t have to have a guilty conscience about disposing of my model organisms in the compost bin after a series of experiments. The other reason for my focus was my former mentor, Dr. Sabine Müller, who has since established her own research group at the University of Erlangen and who did a great job of challenging me and supporting me during my studies and my doctorate. I was never necessarily among the very best at university, but my motto is: “I might not be the brightest candle on the cake, but I still flicker.” That’s also why I tried to find an internship early on in my biology studies, because you can actually get a long way just through sheer hard work. Sabine gave me an opportunity – and sometimes an opportunity is all you need. The internship then turned into a bachelor’s thesis, a master’s thesis and doctoral thesis, all in the space of seven years. Sabine brought order and perspective into my chaotic student life.

DFG: In your research project, you’re looking to explain biochemical relationships in the development of stomata in plants. For non-biologists: what are stomata and what role do they play in plant development or plant life?

AH: Well first of all, the word stomata is the plural of stoma, the term borrowed from the Greek which refers to an opening or pore in the “skin” of plants, the epidermis. Plants regulate their relationship to the environment via these stomata. They need as many as possible in order to ensure optimum gas exchange, but as few as possible to ensure protection from harmful bacteria, viruses or fungi, so there’s a classic trade-off here. There comes a point in plant development when certain epidermal stem cells either develop into stomata or differentiate into epidermal cells. By means of screening it has been possible to identify small bioactive molecules that can specifically interfere with and influence differentiation. We don’t yet fully understand how they manage to do this. Figuring out these processes at different levels – genetic, biochemical, biophysical, etc. – involves classic basic research, but there are translational aspects and potential commercial applications here as well. Understanding how bioactive molecules affect plants is particularly relevant in the context of global warming. Global warming will dramatically exacerbate existing problems such as the increasing resistance of pests to pesticides, the deterioration of soil quality, and dwindling water resources. The possibility of accelerating the required adaptations by intervening in plant biology offers numerous benefits here, including higher carbon sequestration and higher crop yields.

Arvid Herrmann at a presentation

© Privat

DFG: That’s a lot of responsibility on the shoulders of one small branch of science, isn’t it?

AH: It depends a bit on your perspective. Basic research may seem like a small field here compared to the giants of the life sciences such as cancer research, but it is precisely in terms of potential applications that the field quickly becomes huge. Just think of plant breeders, seed producers, or other players in global agro business. And you can also see just how important research into the fundamentals of stomatal development is if you look at where the funding comes from for Keiko Torii’s group here at the University of Texas.

DFG: You’ll have to explain that a little more for those not familiar with the US research landscape.

AH: Keiko receives funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), a private foundation with an endowment of over $22 billion that not only funds the Janelia Research Campus in Virginia but also finances life science research at universities and comparable academic institutions in the USA to the tune of about $1 billion per year. The equivalent in Germany in terms of funding and resources would probably be the Max Planck Institutes. The HHMI promotes what it considers to be important or central to the life sciences. But unlike Max Planck, HHMI doesn’t fund separate institutions but promising individuals. Now money isn’t everything of course, but it is precisely these HHMI funds that create a lot of freedom and allow us to work on a research topic with the necessary human resources and excellent equipment.

DFG: Since it’s a “weed,” thale cress is probably not that expensive. So what do you need all that elaborate equipment for?

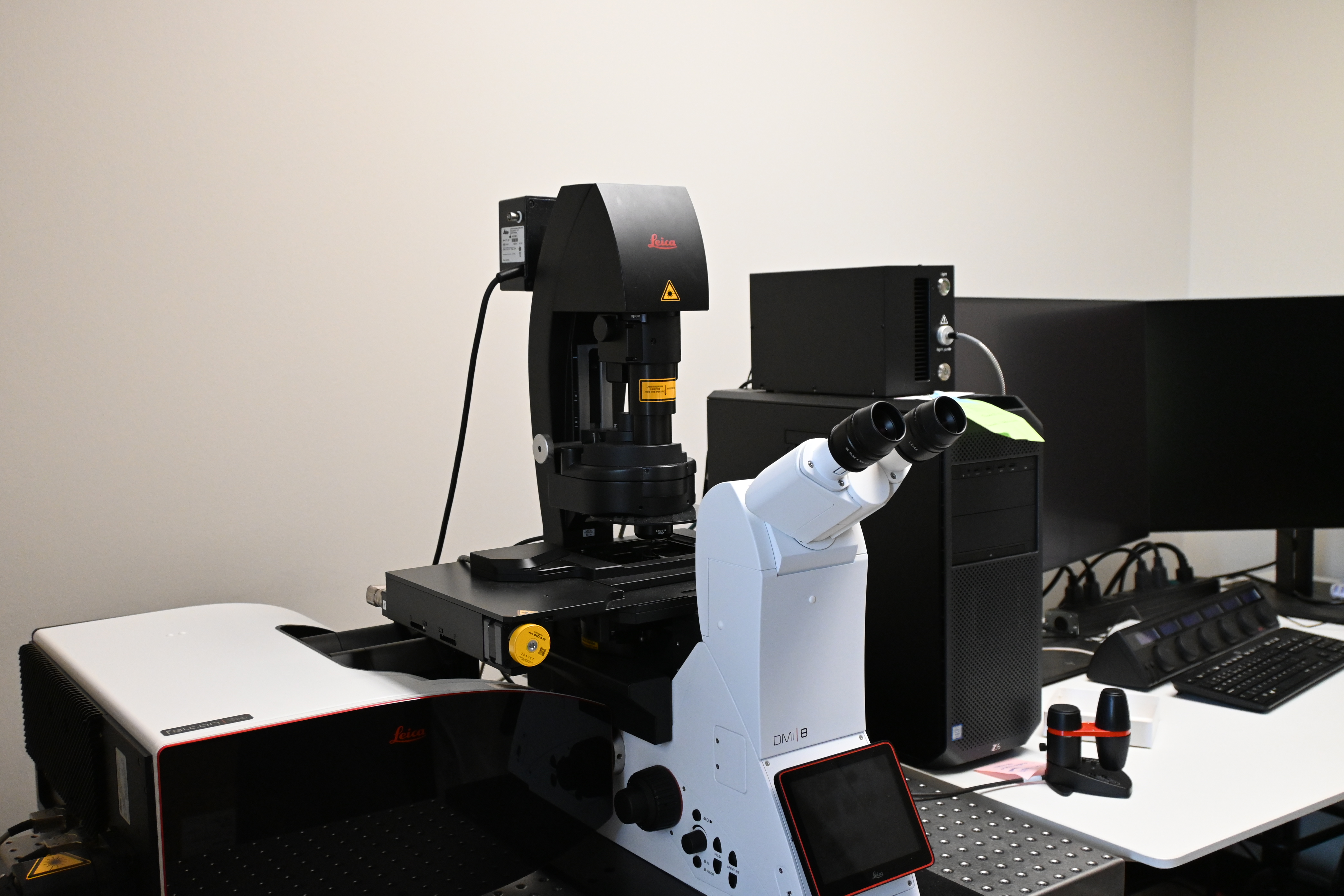

AH: You’re right, you could pick up the object of our research on the grass verge of the main road on your way to the laboratory if you wanted – but you wouldn’t have come up with any publication-ready answers to scientific questions yet. For this you need plant rooms full of genetically precisely defined plant lines, you need laboratory equipment to manipulate the plants and, above all, you need analytical equipment to generate the data. In addition to a number of biochemical and biophysical instruments, these are mainly microscopes, but not the kind you find under the Christmas tree for the very youngest scientists: they are confocal microscopes made by manufacturers such as Leica and Carl Zeiss. Such devices scan the preparation slice by slice with such a low light intensity that nothing gets killed and you can still “see” things. We’ll put that in quotation marks because imaging techniques require not only precise optics but also a lot of calculating and tricks with fluorescent agents. All this makes the devices expensive, so observation times on them are scarce. In Keiko’s group we’re in the fortunate position of having new confocal microscopes made by Leica and by Zeiss, as well as a few older models that are still regularly used and at our free disposal. As I’m one of the few cell biologists in the lab whose research involves a lot of microscopy, I’ve gained a lot of experience and am now officially providing instruction for colleagues on these instruments.

DFG: That almost sounds like a research paradise.

AH: Yes, Keiko is an excellent scientist and her very well-equipped laboratory and support are enabling us to get well established in the field. But she runs her laboratory more according to industrial criteria, meaning predominantly on a results-oriented basis. To put it simply, you have to “deliver” – which can mean a heavy workload, also going in at weekends.

DFG: Weekend work seems to be the rule rather than the exception in the US in general, doesn’t it?

AH: Yes, the notion of a work-life balance certainly sounds American or at least English, but it obviously wasn’t invented in the USA. A ten-hour day plus weekends is considered normal here and is actually taken for granted, especially for all those who come to America on a time-limited visa. I’m not sure if the work is always efficient though: ideas occur to you all the time while you’re working on a project, but the really key issues to tend to come up when you’re showering or jogging – rarely at the bench in the lab. Nevertheless, you tend to spend too much weekend time at the lab and not be noticed by your absence.

UT Austin campus

© Privat

DFG: Not even on Saturdays, when all of Austin flocks to the Longhorns’ football stadium in the middle of campus?

AH: I’ve honestly never been to a football stadium --there’s too much testosterone and drunken American patriotism there for me [laughs]. No, I do enjoy sports myself – that used to be mostly fencing, CrossFit and Zumba – but college sports here in Austin never really appealed to me. It’s more for young students and graduates who are after the thrills – and admission is free for them, too.

DFG: Let’s return briefly to your six or possibly even seven-day laboratory routine. Isn’t it possible to automate a lot of the procedures?

AH: If we were talking about doing things on an industrial scale, then a lot of the manual operations involved in the measurements and even the analyses could certainly be automated, but on the relatively small scale of our laboratory, a lot of manual work is still required, occasionally even tedious repetitive work. We also have to deal with such banal things as mildew, which you wouldn’t find in a modern industrial plant but you do in an old building like the one we have here at the University of Texas. The only thing that helps is disposal, cleaning and moving to other rooms until the ventilation system starts spreading the mildew again. But one key point here is that we’re often groping in the dark in our research. If you wanted to automate processes, you’d have to have a certain idea of where things are supposed to be heading. We always look to enhance efficiency, of course, but the main focus of our interest is on gaining knowledge, not on automating processes – even though that doesn’t make things any easier.

DFG: Where would you like your career to go from here?

AH: In the long term I’d like to stay in academic research and work my way up from the “workbench” into a position where I can develop research questions and the methods to pursue them myself. In other words, it’s fine for me to be a lab mouse right now but I can certainly see a horizon beyond that. Whether I achieve that will depend mainly on whether or not in the time I have left here I can complete the publications necessary to put in a successful application for a research group leader position. The pandemic set me back eight months, which I had to spend in Germany due to COVID-related restrictions on entering the US – after the lab had moved from Seattle to Austin. As you can see, external circumstances can sometimes force you to deviate from your original plan. During this time, my colleagues in Tübingen were very helpful and supportive and I was even able to use their lab at times. The pandemic certainly threw a lot of hurdles in my way, however, and that’s something I’m still feeling the consequences of to this day. But to get back to the question, I’m grateful the DFG has extended the proposal submission deadline for the Emmy Noether Program, for example, so I still have a chance of gaining a foothold in Germany again – hopefully as a group leader, even though the situation is very challenging. But on the other hand, I’m now also known for my precision landings, only achieving a set goal when it really counts. So we’ll see. It seems to me that the trick is to find an ecological niche in science. In Germany, we’re probably somewhere in the middle between diversity and large monocultures.

Modernstes Konfokamikroskop.

© Privat

DFG: Let’s talk about Texas for a moment. How does it feel to live there as someone who grew up in Calw and studied in Tübingen?

AH: Actually it wasn’t even Calw itself but Speßhardt – a hamlet just outside the town – with a population that felt like less than 200. Mentally, this probably isn’t that different from the part of Texas that is rural, which is most of the state. It’s just that the 200 inhabitants of Speßhardt drove to the supermarket with less than eight cylinders under their bonnet, didn’t handle large-calibre shotguns – and none of them wore a huge white hat. But I have very little to do with the rural part of Texas here in Austin, and if you disregard the blazing heat for much of the year, the huge open sky and the very bright light in Texas, you could possibly even think of Austin as an XXL version of Tübingen: an academically and university-dominated and very liberal island in a rather rural environment. Nonetheless, I couldn’t imagine living for a long time in Austin – let alone Texas – and certainly not permanently, despite the great food here in the city.

DFG: Thank you very much for this interview and we very much hope you soon find your way back to Germany, if possible to an environment in which you can build on your research even further to the benefit of us all.